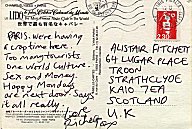

| Just as in his books, Kevin always wrote passionate, precise letters. He always said something of the Important Pop moments that had touched him at any particular time, but one letter stood out. In it he raved about a letter and a record that he himself had received in the preceding week. The record, he said, was somewhat by-numbers-punk, but passionate and unbridled and that was what counts, right? Right. But the letter that accompanied it, he said, was the sort of letter that you carry around in your pocket for weeks. The sort of letter that speaks volumes about intent, integrity, love, hate, desperation and determination; all the key elements of great Pop. Key references were made to what we had assumed to be our canon of inscrutables: Godard, Wire, June Brides, McCarthy, Plath, Jasmine Minks. As Kevin was apt to say, "it all fitted." As well as communicating his excitement, Kevin passed on a name and an address, which is how, in the summer of 1988 I came to write a letter destined for the depths of Wales. It started 'Dear Richey,' A picture of the recipient of that letter is on the cover of the Melody Maker this week (w/e Jan 31, 1998), and the by-line says: "On the third anniversary of Rock's greatest mystery, we ask: What really happened?" Of course they don't know, and add nothing new to the whole affair, aside from possibly adding yet another link to the chain that is 'The Cult Of Richey'. I have zero interest in the Cult Of Richey. I have zero interest in the music of the Manic Street Preachers, a state of being in fact that has changed little over the past nine years. To my mind, musically they were always little more than peddlers of trad-rock banality, and the only thing that set them apart was that the songs were peppered with lyrics which, if slightly 6th form prosaic in form, nevertheless touched on subject matter not often touched on by rock bands. Even this was an aside, however, because what made the Manic Street preachers important was not the what, but rather the how and the why. It continues to be thus. Pop is obsessive by nature, and those who are not obsessive and addictive create and consume what is essentially blandness. Richey understood this implicitly, and it's the reason I felt so closely tied to him through the letters which we exchanged, in the words that trailed between the isolation of Blackwood in Wales and the isolation of Troon in the West of Scotland, in the days before Heavenly and Sounds covers. In those days talk was of the 'Razorblade Beat' (prophetic) and the 'Beat of Violent Sensitivity'. It was of the disgust at Corporate ignorance and the strange, strong pain of being the brutalised outsider. It was of the excitement and inspiration to be found in the books and sounds we devoured in that isolation, celebrating the connections that leapt from inside to what we assumed were some kind of understanding, like-minded souls. A trade of ideas coincided with a trade in words. Words from Rimbaud, specifically from 'A Season In Hell', which we and no doubt a hundred others of the same age at the time were discovering for the first time, and from which I blanche at the sight of my underlining of the passage; 'How strange it will seem when I am no longer here, for I shall have to go a long way away'. Words from Plath, (a personal obsession which drove me to the wilds of a Yorkshire Cemetery a year later), and words from ourselves (Richey's epic 20 page thought poem 'I Am Solitary' may have been, from a critical standpoint, more than a touch self-indulgent, but it had a big impact on me). I always thought Richey was clever, I always thought he was special, and I was sure he was more clever and special than I ever was, would or could be. But he was no more so to me than my other contacts in that invisible network of connecting energies, and when people use the term genius to describe him I balk not at the suggestion that he was, but at the fact that so many who had as much or more talent should be so ruthlessly ignored simply because they were or are less willing to conform to a set of traditional rock expectations. So it was that when stardom beckoned it made no odds to me that he was famous, only that he was talking about things which did not sit easily with what we had written about, and which I suspected he had little real passion for. I was disappointed that public talk was of Guns'N'Roses, and not about the times he'd been to see Talulah Gosh or McCarthy (he told me that he was inspired to join a band by reading the McCarthy/Wolfhounds article in the short-lived 'Underground' magazine, and it was only years later with their cover of 'Charles Windsor' that the nod was finally given), and I was disappointed that nowhere was reference made to the fact that the band name was at least partly as homage to the Jasmine Minks' classic mini-LP '1,2,3,4,5,6,7, All Good Preachers Go To Heaven' (a fact which Jim Shepherd of the band has reminded me of, and which makes me happy that my memory was not playing tricks on me). In retrospect though, that was fair enough. Richey may just have been in the habit of saying what people wanted to hear, me included. It was inevitable then perhaps that we should lose touch. For a while he still mailed records, and the occasional postcard would turn up from Paris or wherever, with a customary sharp quotation, usually of his own pen, but it was no use. The pressures of Pop stardom are great, and besides, I was more into following my own path, fighting my own nightmares and dreaming my own dreams. As Christina once so poignantly sang, "things fall apart". There's a truckload of words both written by Richey, and attributed to him in the seven or so years after we lost touch that I have never read. I have less interest in these words than I have in the ones I have from my own past and the ones that I read in the present from the rare poets I find in the garbage. As said, I have zero interest in the Cult of Richey, and I have zero respect for those who blindly idolise any figure of mass mediated fame. The Cult of Richey, as of any mediated personality, is borne of obsession, and although, as I have said, this is the roots of classic Pop, it is what lies beyond the moment of idolisation, of obsessive collation and collecting that matters most. To take strength from something which shows you to be less isolated than you at first thought, to take inspiration from that and to then say, 'I will create something new of my own, will set my own spirit in flight', to add something new and unique to the story. The battle then remains, of course, as the battle of personal demons and doubts, but at least they are the demons and doubts of your own soul and not the surrogate demons of another. Nearly ten years on from the first letter, things have changed and yet stayed the same. Kevin still writes sharp letters although, like me, with less frequency than previously. He still tells of the inspirational sounds he has unearthed, and when shared they still sound intriguing. Other connections from those times are similarly out there, out of the limelight, searching for new experiences and knowledge, looking for answers to questions they may not even be sure of, but searching all the same. And Richey? I'm sure I don't know, but for what it's worth I don't think he's dead. And also, for what it's worth, I think that people with integrity and love know him not to be dead, to indeed know of his whereabouts and, because of that love and integrity, to be keeping the secret just as long as is required. Long may they keep the secret hidden. © Alistair Fitchett. January 1998.

Footnote: The title of this piece is taken from a song by Wolfhounds, and is a song that Richey said "remains one of the most deeply personal songs I have ever heard." The music press wouldn't tell you this, as he probably never told them, because it does not fit with their cosy concept of the History of Rock. It stands as a fact, nonetheless, in some history, somewhere. |