'Facts' can take care of themselves | |

| I don't want to get into some boring essay about education, but you know I think that the single most important thing to me as a teacher is to make kids aware of the possibilities that are out there; to try and communicate the idea that they are capable of SO MUCH; attempt to pass onto them both the desire to explore further, and perhaps more importantly, the skills that are required in order to set that exploration in motion. 'Facts' can take care of themselves... As can exam results and league tables. I guess if I were to be critical of my own education it would be that I was never made aware of anything very much. Looking back I'm not sure I was ever confronted with possibility. I'm not sure anyone ever really recognised what it was I was capable of and was interested in being (me least of all perhaps); I'm not sure I was ever taken to one side and have the words 'have you thought about...' spoken to me. Maybe everyone was stupid. Maybe they didn't care. Maybe I just didn't have my ears or mind open. Which maybe explains why it was only at 17, on a day trip to the open day at the Glasgow School of Art, sitting drinking coffee in the Vic Café watching some strange duo with guitar and drum machine entertain me and my friend Alan Penman (who strangely is now the bizarre 'Mr P' in the Scottish children's show The Happy Gang), that anything of any possibility ever dawned on me. Which maybe explains why I never really knew who Andy Warhol was until I was 18 and sitting in the GSA library, leafing through a copy of Popism, falling hopelessly in love with the image of Edie Sedgewick. Which maybe explains why then, even though I felt the stirrings of the roots of an obsession springing forth, it was one that never really took off; was one that passed, like so many, into a slight aside. I guess I just never learned how to be obsessed. Which is a lie of course, and I guess what I really mean is that no one ever showed me how to take obsessions further; how to make them more than bland consumption. It was fanzines that taught me that. It was Pop music and the people who wrote about it that made me realise the way the world, MY world, connected together to make a dizzying, magnificent whole. It was people like Matt Haynes and Kevin Pearce, if truth be told, who educated me with more zest and passion than all my teachers, tutors and lecturers put together. It was Lester Bangs, Paul Morley, and yeah, Everett True who made me see that, as Billy Mackenzie sang 'doors lead to other doors, paths lead to other paths.' I quite literally owe those people my life. |

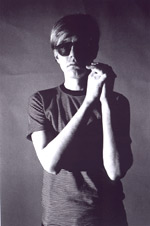

| So Warhol then: one of those artists whose name almost comes into your consciousness without you even realising it. He is such a strange artist, such a strange phenomenon, and I'm aware that a lot of people will be recoiling and thinking me lame and shallow for saying such things. Because, you see, I always feel like I have to be careful with artists. I am constantly aware of my tastes and interests in the visual arts, and worry almost incessantly about whether my love of Warhol and Basquiat is the equivalent of the music bores who extol only the wonders of the Beatles or the Stones and little else. Are my tastes all so horribly obvious? And does it matter that I also happen to love John Virtue's magnificent black and white landscapes of the Exe estuary with their suggestions of Constable and Pollock; that Roger Hilton's collages and paintings make me gooey; that I could look at Peter Lanyon's works forever and a day (and incidentally, there's a Basquiat from 1982 that puts me in mind of the best of Lanyon's later paintings - it's in the red flash amongst the blue and white; the skies cracking open and bleeding, or something...) and never tire; how Sarah Jones' peculiar photos of sulky spoilt teenage beauty ice queens, all full of fragile, decadent despair and myth make me wish that life were... I'm not sure what to be honest. But something OTHER than it actually currently is. That all of those feelings are in fact still just me skirting the Art Top 40, and that in turn puts me in mind of the insert to The Razorcuts' 'Big Pink Cake' single which insisted 'the top 40 isn't where it's at anymore!' Precisely. But still and all. Warhol. I just can't shake the feeling... There's a line at the start of Warhol's America (Thames and Hudson) that suggests "there will always be a pre- and a post-Warhol" and although I'd take exception to the following suggestion that "the post-Warhol period is having difficulty establishing itself" the essence of Warhol being at the centre of some kind of key focal point where culture and society fragmented is one of real truth. It's something I've been banging on about for some weeks now, much to the boredom of my students no doubt: that Warhol is the most important artist of the 20th Century, not so much for the art he produced, but for how he produced that art, how he implicitly understood the essence of Pop as a philosophy; a new method of living, a means of extracting and projecting meaning, of taking the struggle of the Abstract Expressionists to depict an existential spirituality (with all the dichotomies inferred in such a concept) and giving it a uniquely accessible face. For me, Warhol is the ultimate Pop seer, important not because he was the first artist to absolutely see and understand the beauty that lies in the everyday and the potentially ugly or disturbing (you cannot ignore Duchamp, and the best of the DADA artists were of course making a Punk Rock rebellion out of the everyday forty years previous) but because he seemed to naturally understand the movements of history around him, seemed to make connections and commentary on that history on an almost psychic level. Witness his first Marilyn paintings being exhibited almost synchronously with Monroe's suicide, or the celebrated Death and Disaster series throwing a switch that spot lit the underlying sense of desolate existentialism which seemed to be inherent in the troubled youth of America as it passed from the pastel-hued repression of the '50s into the altogether unsettled, unsettling '60s. Warhol seems to me, like Basquiat, early Hip Hop and late post-Punk in America to be an energy both documenting and amplifying the fragmentation occurring in society and culture at the time, and for this he is impossible to resist. |

|

Warhol, it seems to me through his constant socialising (which he always referred to as 'work'), is also the first artist to play a new Art Game, or at least to invent some new rules for the game, and for that I dare say you can either love or loathe him. With Warhol, Art and celebrity entered a new fellowship that would take the previously rather quaint, reserved and informed approval of the likes of Picasso and Dali towards the altogether more vulgar adoration of Schnabel, Koons and Hirst (You can make your own decision about whether 'vulgar' here is a compliment or not). Not forgetting of course the ultimate crucifixion on the altar of celebrity excess; that of Jean Michel Basquiat ... Naturally the Abstract Expressionists had started to pave the way, notably with Pollock and his 'live it like you paint it' approach to existence and, ultimately, end of existence; and although it was Jasper Johns (and incidentally, listen out for Comet gain's magnificent song for the great man on their Tigertown Pictures album), Robert Indiana and Robert Rauscheberg who were among the first to bring a figurative element back into the avant garde, it was Warhol who had what it took to take the avant garde of painting and make it accessible to a world that was not made up of other artists or art critics. Warhol was of course aware that the 'importance' granted to individuals (be it rock and roll stars, movie stars, aristocrats or painters) is built on myth, and more than this he implicitly understood that the self-invention of mythology was an essentially Pop Thing. It is this understanding of the myth-making process that has led to Warhol's working environment, more than any other artist, being the subject of so much documentation. If you take away the Factory from the Warhol story you effectively are left with nothing very much at all: 'simply' some beautiful, relevant paintings that might make you conjecture that Warhol was a great colourist. But who ever wanted to read about great colourists? |

|

And having said that of course I don't quite believe it because there are terrific works from the 1980's such as 'Moonwalk', 'Beethoven' and the Lenin series that are fascinating for their predictions of the kinds of digital imagery made possible by graphics packages such as Photoshop. I'm convinced there is an intriguing essay to be penned which looks at the connections between Photoshop and the work of artists such as Warhol, Sigmar Polke and David Salle, all of whom have shown in their paintings from the early 80s onwards, the sorts of explicit floating of layers of imagery with transparency which Photoshop would later make so easy. Further interest is then in considering the impact of image-manipulation in a post-Photoshop world; certainly Rita Ackerman's seductive paintings from the early '90s suggest some kind of awareness, but that might just be because I am a bit of a computer bore.

But back to The Factory, and the fact that is the hordes of 'Superstars' (and according to Rene Ricard, the term 'Superstar' is found in only an obscure 1930s movie fanzine before Warhol and Baby Jane Holzer coined the term - it's a nice tale) who passed through its doors who are in effect the real interest in the Warhol story: it is the way in which Warhol interacted (or more accurately, observed and manipulated) with these characters that in essence IS Warhol; the Factory with its itinerant inhabitants becomes, quite literally the process of Warhol's work. Or at least it does if you ignore the bread and butter portraits he produced to pay the bills... What is interesting in the documentation of the Factory (and there is a lot!) is how successfully Warhol was able to use the media of photography to create his myth. Billy Linich / Name is the one most recognized with documenting the Warhol Factories and rightly so, since it was he who designed the infamous silver décor of the first Factory, and he who lived in the bathroom of the second, devoting himself to ancient mysticism and surviving on flat foods, and I often wonder if Douglas Coupland got his idea for the sliding food under the door segment in Microserfs from Billy Name. I bet he did. Matthew Collings notes in his book It Hurts that every Warhol biography always ends a chapter with Billy leaving the Factory without notice one day, leaving only the note. 'I have gone. I am fine.' Or something along those lines. Collings gets it wrong, as have I, because it doesn't really matter. It was the punctuation point of Billy leaving that really mattered. |

|

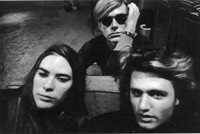

It was, and still remains, Billy Name's (and to a lesser extent Nat Finkelstein and Stephen Shore's) black and white photographs that most people, if they have an interest at all, think of as the lasting images of the Factory. It all looks so strangely glamorous; a decadent marvel of reflective silvered light and deep shadow, and even though you just KNOW that everything must be dusty and dirty and that there's no way you'd want to sit on 'that' couch, you cant resist the feeling that in fact there's nothing you'd want more than to sit on 'that' couch. And there's the key to the success of these photos as historical myths; that high contrast of blanched out whiteness and heavy shadow, casting the geometry into sharp focus and blanking out the imperfections. It's all a magnificent lie.

More interesting that the black and white shots, however, are the collections of colour prints that have recently seeped out of the woodwork. Nat Finklestein has some in his Andy Warhol: The Factory Years (Canongate) book, and they generally look great. Seeing Edie in colour for the first time is a revelation, and she still looks fantastic. In fact there's two shots in there that are now my favourite Edie photos, but best of all is a shot of an unknown figure leaning on a phone at a Malanga poetry reading; a real Beat angel, which some would say is a dreadfully shallow thing to be saying but I don't care. And speaking of Beat angels, how about the figures in Bruce Davidson's Brooklyn Gang (Twin Palms) book? All tattoos and DA haircuts, looking like the wildhearted outsiders of the finest rock'n'roll mythology like Eddie Cochran and Gene Vincent (do you get it yet? All of our Pop lives are built on mythology - the key is that you create your own from others'). Look at the photos and see the wonderful picture of Cathy fixing her hair in the mirror of a cigarette machine down at Coney Island and then read the text at the back of the book and want to weep a billion tears, and you think of Kenny Wisdom and you think of all the lives lost and isn't life such a tragedy? Billy Name's collection of photographs from the second Factory on the other hand (collected in All Tomorrow's Parties (Frieze)) are much more revelatory than Finkletsein's. Name's photos do the opposite of his black and whites; they explode the doomed romantic imagery of the scene and replace it instead with a seedy Polaroid vision with all the traces of abuse and decay firmly in place. It's nowhere more obvious than in the pictures of Nico; the ice queen of cool in the black and white shots is transformed into a blemished desolate zombie, which is no criticism per-se of course because hey, all people DO look less than perfect some of the time (I assume they do - the truth being otherwise is too much to bear), but it's a shock nevertheless. This is what drug use and abuse does to you kids... it's not a particularly pretty sight. |

|

Best of the Name colour photos, however, are a sequence of images showing a variety of people leaving the toilet at the Factory, some of them known, some of them not. There's Paul Morrissey, Viva, Joe Dallesandro (and incidentally only Joe survives the book looking like the beautiful Star he always seemed to be; everyone else looks so rough it hurts, and The Velvets on the couch look so downright STRAIGHT they look weird), Rene Ricard, Brigid Polk and there's Andy himself, wiping his hands on a paper towel. And there's Vera Cruz... a satellite member of the Warhol entourage not widely known, except perhaps to anyone who has had the good fortune to read Mary Woranov's great Swimming Underground (Serpents Tail), in which case you'll know all about her and her strange obsession with Woranov which just about sent Mary mad with hatred.

Swimming Underground is my favourite Warhol book because it doesn't try and give me the kind of creepy smug completeness that Victor Bockris does with his Life and Death of Andy Warhol (still essential reading, regardless, although be prepared to fumble with the contradictions that incessantly crop up), and it doesn't have the naturally defensive stance of Popism, and whilst we're on the subject of contradictions and defensive statements, which do YOU think is true: that Warhol GAVE an Elvis painting to Bob Dylan after his visit to the Factory, or that Dylan simply lifted one on his way out? I know which story I prefer to believe... Mary Woranov was of course a member of the original Exploding Plastic Inevitable, dancing with Gerard Malanga and whips in front of the Velvets when they played their Uptight performances, and of course too a star of the Chelsea Girls movie. Her account of her time in the Warhol Factory is compelling, not just as an insight into a particularly vital moment of Pop history, but also as a personal exploration of a fractured life and the waywardness associated with searching for something to fill the void. It's a terrifically entertaining afternoon's read. |

| It's interesting that Warhol, the classic voyeur, has become the artist whose life people seem most interested in looking into. There's not the same sense of mystique around the blatantly self-referential, autobiographic angst of Tracey Emin, say, (and not just because of a lack of 'historical perspective') because Tracey doesn't keep her distance from her work and Warhol always did (is that a good or a bad thing?), and in fact there's no one else I can think of who can even begin to get close in art circles, either from the past or the present. Maybe Van Gogh because we all like a bit of madness and maybe Basquiat because he was so good looking and drugs are always a good story to hang a sale off of... but no-one compares to Warhol. No-one compares to Warhol because no-one else has been at the absolute centre of a cultural shift the way he was; no-one compares to Warhol because no-one else has wanted to turn the mirror back on the world and show it the ugliness and beauty it possesses with quite the same degree of detached observation as he did (everyone else seems to want to make an issue out of it); no-one compares to Warhol because no-one else at the time seemed to prefer the raw ragged vicious howl of the Velvet Underground to lazy hippie love-fests; no-one compares to Warhol because no-one else outside of the best Beats seems to have said 'the outsiders are the true desolate saints of our world' with such clarity; no-one compares to Warhol because no-one has left so many beautiful corpses in his wake. And no-one compares to Warhol because no-one else seems to have created a personal mythology as successfully as he. 'Facts' can take care of themselves... © Alistair Fitchett 2001 |