Of Critics and Cannibals | |

| "The hardest movies to defend are those that everyone loves." That's the kind of line only a film critic would write. Correction: the kind of line only a very good film critic would write--one honest enough to admit that there is indeed a certain pressure among serious critics to always be leery of the hugely successful and/or sentimental film, to always keep a healthy distance from cinematic populism. The sentence was written by Dave Kehr as an introduction to an essay on director Robert Zemeckis in the March/April, 1995 issue of "Film Comment." More specifically, Kehr was writing about Zemeckis' "Forrest Gump," one of the most commercially successful films of all time. While the movie certainly earned more than its share of good notices (from real cinephiles and hacks alike), its detractors saw it as either overblown sentimentality or, far worse, as covert propaganda intended to condemn the activism and social liberalism of the 1960s and reassure Baby Boomers that political ignorance and "traditional values" were the keys to heaven. As one would expect from one of the country's best film critics, Kehr did not take refuge in "Forrest Gump's" uncanny ability to warm the collective heart of middle America. Instead, his article argued persuasively for appreciating the film in the larger context of Zemeckis' work, for its sheer narrative ambition and for the subtle dark shadings that most viewers chose not to see. For, while Kehr's opening line acknowledged the burden of the serious critic to be a constant advocate of the under-appreciated, the little-seen, the challenging, the old, and, of course, the foreign-made; it in no way rejects that burden. In an age where more and more entertainment industry publicists masquerade as film critics (and are accepted as such by much of the public and the media), no one knows better than Dave Kehr that a little bit of professional peer pressure--a degree of cultural obligation--is not only healthy, but essential in an environment of ever-increasing marketing dominance. In case you haven't guessed by now, I like Dave Kehr. He is, in fact, my favorite film critic, even though his move from The New York Daily News (who showed him the exit in a troubling, all-too familiar sign of the rapidly diminishing space for serious criticism in mainstream publications) to the woefully paperless World Wide Web (as critic for CitySearch.com) means I see less of his work than I used to. Kehr has been my favorite critic for well over a decade, dating back to the years when he was the main reviewer for The Chicago Tribune. He was even my favorite critic on February 14, 1991, when, as befitting a Valentine's Day, he broke my heart with a devastating, one-star review of "The Silence of the Lambs." |

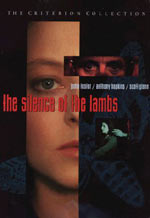

| Nearly a decade has gone by since that review was published, and my tastes and film vocabulary have certainly expanded and, in some ways, changed in the interim. Some of the films I loved as a 22-year-old, second-year film student mean far less to me now. Not "The Silence of the Lambs" though. Its satisfactions--as both an entertainment and as a profound statement on the human condition--have only magnified over the years. Since its release, I have watched it at least once a year (most recently with the excellent Criterion edition DVD) and it is one of those true rarities that improves with subsequent viewings. Of course, the film hardly needs my endorsement. Like "Forrest Gump," it was a box-office blockbuster and a multiple Academy Award-winner. And its villain/hero, Hannibal Lecter, became an instantly recognizable pop culture icon--his chilling stare as familiar as Forrest sitting at the end of his park bench; his sinister one-liners quoted nearly as often as "Life is like a box of chocolates." "The Silence of the Lambs" was also critically acclaimed. Well...sort of. Amid the tidal wave of accolades the film received, there were, of course, contrary opinions. Most of these meant little to me. Many were written by impotent moral guardians--Michael Medved-ites preaching the poison of ignorance under the banner of protecting children. This was familiar nonsense propagated by those whining for easy and contradictory answers: labels and ratings instead of media literacy education, condemnations of shock radio and sex on TV while simultaneously calling for cutbacks in public broadcasting funding. Most of these "Silence" bashers were easily dismissed in my mind. But not all of them. In Chicago, where I live, Kehr and the invaluable Jonathan Rosenbaum of "The Reader," condemned the film in the harshest of terms; challenging neither its technical nor dramatic merits (both admitted they were considerable), but its moral standing. When reliably liberal minded critics bash a film for its moral standing...well, at least you can safely label the movie as provocative. Yet the response the film provoked in me when I first saw it in an overcrowded suburban theater was as different from the response of Kehr and Rosenbaum as it could possibly be. I can pinpoint the precise moment when "The Silence of the Lambs" became far more than "entertainment" for me. It occurs during the scene where the FBI agents perform a post-mortem examination on the body of a victim of Jame Gumb, the "Buffalo Bill" serial killer. It is the moment when Clarice Starling (and she was, for me, truly Clarice Starling, not Jodie Foster) musters up her courage and turns around to face the ultimate cruelty one human being can visit upon another. Fighting back tears, determined to honor this horrifically brutalized woman with her own dedication to the case, she proceeds with utter professionalism. In those few overwhelming seconds of Clarice's adjustment, my film school education became irrelevant as I "bonded" with this fictional creation. Like Antoine Doinel's final look into the camera, out at the audience, at the end of "The 400 Blows," Clarice's moment of decision, of understated trauma, startled me with its intimacy and depth of feeling. |

| When the film ended and the credits began to roll, I noticed that most of the crowd was staying in their seats--a rare phenomenon outside of art film venues. Part of this can be explained by a clever manipulation by director Jonathan Demme. The film ends with a continuous single shot of a Bahamas street scene. The ingenious killer Hannibal Lecter, casually walking down that street, stalking his next prey, is the last plot-driven image. Even though Lecter has already been lost in the crowd when the credits begin to roll , the long-held shot and the film's unresolved ending promises more to come. Although the audience surely sensed nothing more would happen (at least until a sequel), the shot maintained a quietly suspenseful hold on them. But it was more than this. The audience stuck around to share in the electricity of the experience...to hear the excited murmurs of fellow audience members. The movie had them. Sadly, I was to find very quickly that, while the movie had them, it didn't quite have them the same way it had me. Walking out of the theater, the bits of conversation I picked up were all about Hannibal the Cannibal. Wasn't he scary? Wasn't he creepy? Wasn't he funny? And yes, he was. He was scary, funny, charismatic...the greatest movie monster in ages. But what about Clarice? Before the week was out, it was clear that Hannibal Lecter, not Clarice Starling, had won the hearts of America. His dialogue was repeated endlessly, the ominous voice of Anthony Hopkins imitated everywhere from grocery store lines to late night talk shows. I saw the film again the next week and discussed it with others who shared my worries that audiences were only seeing a slickly produced (albeit especially well-made) thriller and not the meaningful emotional offering we had experienced. Rereading the reviews of Kehr and Rosenbaum only made things worse. "More than a disappointment, the film is an almost systematic denial of Demme's credentials as an artist and filmmaker," wrote Kehr in the Tribune. "It's a gnarled, brutal, highly manipulative film that, at its center, seems morally indefensible." Rosenbaum was no kinder in the Reader: "An accomplished, effective, grisly, and exceptionally sick slasher film that I can't with any conscience recommend, because the purposes to which it places its considerable ingenuity are ultimately rather foul." Kehr's review hurt worse, not only because he was my favorite critic, but because he expressed such admiration for Demme's earlier work. In his "Silence of the Lambs" review, he compares the humanity of Demme's prior films to the work of Jean Renoir. For him, this movie was a betrayal of that humanity, and its technical assurance only made the betrayal sting more. He closed his review with absolute condemnation: "...the way the killer holds his victim is the same way the director holds his audience, through threats and intimidation. This isn't the Jonathan Demme we know." |

| Although it suggests an identification with the audience, Kehr's communal "we know" was, and is, a troubling phrase. A critic's assumption that his or her readers relate to a film in the same way he or she does is always a dangerous one. The line also reveals a rather rigid interpretation of the auteur theory, suggesting that if a director radically changes his visual, narrative or thematic approach, the change must signify a compromise and the film is therefore doomed to be labeled as a less personal work. Of course, it is an interpretation that is only useful if you don't happen to like the change. If you like it, it becomes far more comfortable to discuss the change as "artistic growth," or the director's "reconsideration" of past strategies. Admittedly, I came to Demme much later than Kehr. "Something Wild" was my introduction, so perhaps my acceptance of Demme's darker, coarser side was easier. But even after seeing "Melvin and Howard," "Handle with Care," "Last Embrace," "Swing Shift" (although perhaps Goldie Hawn's hijacking and butchering of the film should disqualify it as a Demme film) and "Married to the Mob," I had no trouble seeing the same Jonathan Demme in "The Silence of the Lambs." This was definitely the Jonathan Demme that I knew--an eclectic, consistently engaging filmmaker whose work always demonstrated a deep empathy with his characters. After all, Demme's style has always been in flux. The early bargain-budgeted exploitation pictures for Roger Corman ("Caged Heat," "Crazy Mama," "Fighting Mad") certainly don't closely resemble the glossy Hitchcock homage "Last Embrace." And both "Something Wild" and "Married to the Mob" rely on fluid, flashy camera movements more than the laid-back "Handle with Care" and "Melvin and Howard." So, while one can certainly express a personal distaste for the extreme close-ups, the hyper-dramatic lighting and harsh imagery of "The Silence of the Lambs," the argument that the director's choices were commercial compromises are somewhat dubious. On the audio commentary for the Criterion edition of "Lambs," the always modest Demme speaks of his efforts to be faithful to the tone of Thomas Harris' novel. While his films are far too interesting to dismiss him as America's Merchant-Ivory, he has consistently shown a refreshing willingness to alter his stylistic "signature" to suit his material. While both "Philadelphia" and "Beloved" bear a strong stylistic resemblance to "Silence of the Lambs," Demme continues to toy with other techniques in his diverse body of non-Hollywood work, such as the intimate documentary "Cousin Bobby" and the unfairly ignored concert film "Storefront Hitchcock." Thrillers and horror movies are, almost by definition, more manipulative than other kinds of films, so in that sense there is no arguing when Kehr writes, "The Silence of the Lambs is a film that exerts a vice-like grip on the viewer; it's as closed and claustrophobic as Demme's other films have been open and democratic." Still, nearly ten years later, I continue to find Kehr's ideological reading of Demme's strategies problematic. Take "Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer," a film Kehr wrote favorably about, preferring its gritty realism to the Demme's gothic fantasy. Is it really any less manipulative because it avoids shock cuts and extreme close-ups? Amy Taubin, in an excellent piece on serial killer movies in "Sight and Sound" expressed feelings that I share concerning John McNaughton's disturbing feature. The movie's most infamous scene is the videotaped massacre of a family, shown exactly as it is supposed to have been shot by killers Henry and Otis. The worst violence occurs after Henry drops the camera, and the audience is forced to endure a long shot of the unedited violence: no grisly close-ups, but far more horrifying than anything in "Silence of the Lambs." The scene has been defended as a commentary on voyeuristic violence, forcing the audience into an uncomfortably objective point of view. In her article, however, Taubin sets the record straight, describing what McNaughton shows immediately after the "objective" videotape sequence: |

| "Cut to Otis and Henry sitting side by side on the couch, relaxed and bonded like two regular guys watching football. 'I want to see it again,' whines the infantile Otis, hitting the slo-mo button on the remote. The camera zooms languorously past their attentive faces towards the TV screen. There is no doubt about whose eyes we're looking through, and as the scratchy theme music swells above the woman's screams, no doubt, either, about where the director's sympathies lie." Too hard on McNaughton? Maybe. It's certainly no harder than Kehr was on Demme. It's not that I think Kehr is a less sensitive a critic than Taubin, but concerning this particular film, she seems to me far more on target. Her article provides a deeply thoughtful emphasis on the significantly feminist subtext of "The Silence of the Lambs," an essential part of the film which Kehr dismisses quickly as Demme's "alibi." A far more subtle, but still important, subtextual reading of the film that Taubin also picked up on was the equation of American militarism and patriotism with the random, senseless violence of serial killers. A huge American flag is draped over the car where Clarice finds the severed head of one of Buffalo Bill's victims. A Senator's daughter, soon to be taken prisoner by Buffalo Bill, sings loudly and proudly along as Tom Petty's "American Girl" plays on the radio. Later, a police officer is killed by Lecter and strung up with the red, white and blue streamers that adorn a courthouse. In terms of plot, this makes no sense: the idea that Lecter, planning his escape, would take the time to create this elaborate crucifixion scene is absurd. But it's a powerful image, continuing a visual motif that culminates during the movie's final confrontation, when sunlight finally breaks through on Buffalo Bill's hide-out, revealing artifacts suggesting Bill was a Vietnam Veteran or a collector of military memorabilia (we also briefly see a comforter with a swastika emblem and other Nazi items). Taubin may have ultimately seen more in these details than even the director intended, but any suggestion that Demme was not aware or concerned about the thematic value of these carefully placed images is ludicrous. While it is always dangerous to take the word of an artist after the fact, the director's commentary on the Criterion disc certainly supports Taubin. Kehr, who is usually an observant critic, did not mention these subtle pokes at militant Americana in his original Tribune review, nor did he take note of them in an extended essay about the film that ran in the paper on March 10, 1991. In that essay, Kehr took time to criticize Taubin's feminist reading of the film, arguing that it doesn't acknowledge the severe manipulations Clarice suffers from both Lecter and her FBI boss Jack Crawford. However, he does not take the time to detail the film's many representations of sexism, as Taubin did in her "Sight and Sound" piece, or as Kathleen Murphy did in a "Film Comment" essay (January/February, 1991). Unlike the film's inverted flag-waving, the critique of sexism and patriarchal failings in The Silence of the Lambs is quite apparent. To cite just a handful of examples: |

| 1) Clarice in an elevator, surrounded and dwarfed by her male FBI counterparts. 2) On the FBI training ground, Clarice and a fellow female student drill each other for a test while jogging. A group of male trainees, significantly jogging in the opposite direction, turn as the girls pass to check them out. 3) The grotesque come-on by Lecter's creepy psychiatrist-jailer: "Will you be in Baltimore overnight? Because this can be quite a fun town if you have the right guide." 4) Clarice assaulted with the ejaculate of one of Lecter's neighboring madmen--the same wolf-like creature who greets her entry into the institution with "I can smell your cunt." 5) Lecter's knowing, malicious jabs at Starling's sexual discomfort as a youth: "All those tedious, sticky fumblings in the back seats of cars..." 6) The judgmental stares of the local police at the small town funeral home upon seeing their first female FBI agent. The awkwardness is only accentuated when Crawford pretends to be protective of her sensitive, feminine nature to get past the sheriff. 7) Lecter's cruel misogyny as he tauntingly "corrects" Clarice. Lecter: "What does he do...this man you seek?" Clarice: "He kills women." Lecter: "Nooo. That is incidental." 8) Matching close-ups: Lecter's hand as his finger brushes against Clarice's and then Crawford, near the end of the film, extending a congratulatory handshake to his student--two male mentors who have used her dedication as a device to their own ends. Kehr suggests that because Clarice does not triumph over Lecter, because she "allows herself to be raped, mentally if not physically, in exchange for the male's superior intelligence and insight" she cannot be viewed as a feminist heroine. This is almost a Hays Code interpretation: the good guy must always win, evil must always be punished. Clarice is a strong symbol of feminism precisely because she is also a survivor of male domination. However much she is toyed with by Lecter, she remains true to her mission. Her moral crusade retains it integrity even in the film's terrifying final moments, when she realizes Lecter is loose and the lambs are again in danger...forever in danger. In this regard, Taubin's view that Clarice is "...a hero rather than victim, the pursuer rather than the pursued" does seem a little too hopeful, just as Kehr's positioning of her as a mere portal for Lecter's wisdom is too narrow. This is a rich character, filled with virtues, flaws and contradictions. Isn't this what we always look for but rarely find in Hollywood movies? While she is certainly charged with rich symbolism, must we reduce her to a mere statement? What's most vexing about Kehr's rejection of the movie's social and political subtext is his insistence that, rather than trying to infuse a commercial genre with deeper meaning, Demme was only constructing excuses for a vicious exploitation film. In his second Tribune piece on the film, he negates any sincerity of feminist motivations in the film, calling it "an interpretation Demme himself has clung to in his interviews." "Clung to?" That phrase suggests some sort of desperate, last-minute cover-up when Demme realized he had made a gruesome, tightly wound film. Beyond its insult to Demme's character, the comment also calls into question his alertness to his craft, as if the film's content and its reception surprised him. Kehr wasn't the only critic willing to impose his own feelings about the film upon the director. In a fastidious yet occasionally cockeyed analysis of the "B" movie aesthetic in "Film Comment" (July/August, 1993), Gregory Solman pretty much sides with Kehr's view of "The Silence of the Lambs" and makes a similarly offensive assumption: "Pressed into self-scrutiny, Demme himself might admit this film was a breezy limousine-liberal's ride back to Corman country." Well, then again, he might not. But until we film critics perfect our psychic ability to read the motivations of filmmakers, perhaps we should try to stick to what is on the screen. Obviously Demme was aware of the genre he was working in, its lowly reputation and its guilty pleasures. Corman country? Yes, in so much as the film, at its most superficial level, is a good B-movie potboiler. And hey, guess what? Roger Corman even pops up as the FBI Director, so apparently Demme didn't need to be "pressed" to acknowledge the influence of his former mentor, the "King of the B's." But it is strange that, in an article where Solman defends "Jurassic Park" as "Spielberg's elegiac plea for humana vitae in a world obsessed with genetic engineering," that he also can't find a similarly open-minded view of Demme's blurring of art and entertainment. At the very least, Solman should be willing to concede that Demme's defense of his movie is as valid as his own rather esoteric view of Spielberg's dinosaur movie. As for the snide "limousine-liberal" remark, well, Spielberg was chartering limos long before Demme, and mining "Corman Country" with far greater regularity. |

| The "Silence of the Lambs" was also attacked in many quarters for its allegedly homophobic portrayal of Buffalo Bill. It's an issue worthy of debate. Demme acknowledged in a "Premiere" magazine article (January, 1994) about the making of "Philadelphia" that he had homophobic beliefs growing up. Despite personal friendships and social and political awakenings that ended those beliefs, it could be argued that, in bringing Buffalo Bill from the written page to the screen, Demme reverted to the damaging stereotypes of his youth. After all, the killer wants to transform himself into a woman and has experimented with transvestism before moving on to skinning women. To top it off, Buffalo Bill is a talented seamster who even owns a poodle named Precious. However, while the film never expressly states that Buffalo Bill is not gay, it does firmly say that he is not a transsexual (Lecter explains Bill's almost schizophrenic pathology in detail to Clarice), which--if the viewer accepts the diagnosis--diminishes the character's stereotypical aspects. And how much of this interpretation of Buffalo Bill is contextual? In 1991, fear of AIDS was immeasurably greater than it is now, while positive portrayals of homosexuals in mainstream culture were still marginal at best. If the film were released today, in the more open environment of TV's "Will & Grace" and post-"Philadelphia" tolerance, would Buffalo Bill be viewed as such a damaging representation, even if one does take him to be gay? If the day hasn't yet arrived when movie villains can be heterosexual or homosexual without casting aspersions on all people with the same sexual preference, we are certainly closer to it now than in 1991. Having spent most of this essay picking apart various objections to "The Silence of the Lambs," let me now put down the gloves and state the obvious. No matter what subtext you choose to see or not to see in the film, it is undeniably a movie in which a serial killer is afforded hero (or at least anti-hero) status. It is a film that revels in the grotesque and that romanticizes evil as much as it condemns it. And there's nothing new about that contradiction. Audiences thrilled by "Psycho" over the last 40 years rarely consider the real-life atrocities of serial killer Ed Gein that were the inspiration for Robert Bloch's book which was the basis for Hitchcock's film. Few people link the vampire fantasy of Dracula with the historic figure of a violent 15th Century Transylvanian prince who may have dined in front of the speared bodies of his enemies. But those connections exist. Writers, artists, dramatists and filmmakers have always and will always walk, and sometimes stumble, on that line between the allure and fear of wickedness. The "Silence of the Lambs" is, in the end, a disturbingly conflicted movie. If one wants to dismiss it, it can even be described as hopefully at odds with itself, compromised by two very different moral outlooks. Yet, it is exactly this schism that makes the film special, timeless...worth arguing about. The film mirrors the peculiar symbiotic state of human existence, that troubling flirtation between the better angels and inner demons of our nature. In fact, at this point in history, it is fair to say that it is less a flirtation than a marriage. As Lecter says to Clarice, "People will say we're in love." Still, even though I'm now more comfortable with the universal appeal of Hannibal "The Cannibal" Lecter, and even though I've learned to accept my favorite film critic's hatred of the movie, I can't help but feel that somehow, nearly everybody--Kehr, Taubin, Rosenbaum, Solman, the guy at the corner store--is missing what I get out of it. And that is pure, basic, overwhelming sadness. "The Silence of the Lambs" is a film about eternal mourning and worry. Its qualities as a thriller, as a horror film, as a feminist statement, as a social and political critique, all pale next to its moving portrait of a woman forever traumatized by the death of her father, who transposes that trauma onto the death of every innocent in the world. She is courageously committed to a war she knows she can never win. The monsters will always be out there. Thankfully, I stumbled across J. Hoberman's review of the film from The Village Voice, included in the National Society of Film Critics' collection "Love and Hisses" (Kehr's second Tribune essay on the film is included as a counterpoint). Hoberman finally put in print what I felt, what I still hope, every viewer should walk away from the movie with. "Given the shock material and Demme's visceral direction," he wrote, "the movie is unexpectedly affecting, with its burden of grief unusual for its genre; beneath the narrative, there's a river of tears...Ultimately, what makes "The Silence of the Lambs" so potent is the heroine's inconsolable unhappiness, her solitude and sense of abandonment, the rescue fantasies she nurtures, the defensive posture she's forced to maintain." Perfect. Why couldn't I have picked up The Village Voice that frustrating week in February of 1991 and found this articulate, beautifully written expression of what, to me, the film will always be about? And now we have "Hannibal." Since "The Silence of the Lambs" was, in a sense, itself a sequel (following Michael Mann's underrated "Manhunter," based on Harris' novel "Red Dragon" and featuring Lecter in a smaller, but still pivotal role, played by Brian Cox), it is probably unfair to come in with low expectations for this belated and seemingly unnecessary follow-up. Still, the early signs are not good. Demme and Jodie Foster passed on the project, both apparently feeling Harris' new novel lacked the humanity of its predecessor. Anthony Hopkins returns, certain to grab the spotlight for Lecter even more fully. Perhaps the gifted Julianne Moore can pull off the impossible and make Clarice Starling her own, erasing the expectations Foster established for the character, but it's a tall order. And the technically polished Ridley Scott, fresh off of "Gladiator," hardly seems the right man to succeed Demme. Scott can execute production values with the best of them, but the emotional content of his pictures is often distressingly thin. It's been 18 years since Scott's masterful "Blade Runner" and he hasn't been getting better. I expect more "jumps," if not more genuine scares, and certainly more black comedy courtesy of America's favorite psychopath. But if Scott and company even come within striking distance of the "river of tears" in Demme's film, I'll be pleasantly astonished. Just as the four, increasingly cartoonish sequels to "Dirty Harry" gave some critics the excuse to ignore the complex psychology of the original film, I fear that an empty, thriller from Scott will provide the same alibi for those who want to dismiss "The Silence of the Lambs." I hope that's not the case. It is a film that deserves thoughtful consideration, whether one ultimately embraces or rejects it. Oddly enough, I once rejected the film myself, in a small but telling way. At my workplace, several staffers contributed an "All-Time" favorite movies list to commemorate the end of the 20th century. While the last thing the world needed at that time was another movie list, our minor offering (posted on the company website) was at least an enjoyably diverse selection, with each participant selecting 25 films with no criteria other than personal taste. And yet, I excluded "The Silence of the Lambs" to make room for Walter Hill's somber western "Geronimo: An American Hero." Thinking very much like a critic, I wanted to promote another American studio film from the same decade that I felt was overlooked and underrated. And, I must confess, in an arts-centered environment, I was self-conscious about choosing such a massively popular, well-known film that had, after all, earned the ire of my favorite film critic. And so, I omitted what is undoubtedly one of my 25 favorite films. Kehr was right. The hardest movies to defend are those that everyone loves. © Joel Wicklund 2001 Joel Wicklund is a freelance film critic and a staff writer for Facets Multimedia, a non-profit media arts organization based in Chicago, Illinois. |