Instant Access | |

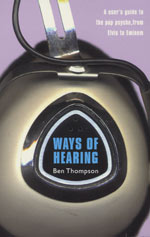

| '...why, when scientology claims to open up the hidden chambers of the intellect, does pop offer instant access to areas of the mind L. On Hubbard could only dream about?' asks Ben Thompson in the 'Mission Statement' that opens his new book Ways of Hearing (Orion, £14.99). Pop here, for Thompson, is taken to mean 'songs as experienced through the filter of what is sometimes rather off-puttingly termed The Pop Process'. Interestingly, Thompson is aware that both the book and its author are part of this very process: '[Ways of Hearing's] raw materials were gleaned through the sinister business of writing interviews and record reviews for newspapers and magazines, and inevitably - and properly - bear the mark of these devious mechanisms.' So what does Thompson offer us from the heart of the beast? On one level simply essays and interviews; but it's the knowingness of Thompson that is so intriguing. He doesn't distance himself from his subjects - he likes music too much to do that; nor does he mock and scorn - he's no sneering ranter; but the reader can sense that Thompson is not fooled by the transitory, elusive nature of pop and its purveyors. This transitory nature, the coming and going of musical styles, subcultures and stars themselves, informs Thompson's overview. He delights in contextualising what he's interested in, in pointing out the sources and strands of influence that have gelled to make the pop music under scrutiny; he delights in discussing the game of Pop with those clued-up enough to do so: Eno, Pet Shop Boys, Robert Wyatt; and he is good at stepping back from his subjects to see exactly how they can be seen, if at all, in the big bad world around what is, in the end, the little world of pop. Wrapped around the interviews at the centre of the book are two sets of essays which help the reader to join him in doing this. The opening five are on music's relationship to other media: Radio, TV, Film, Video and Books. All are perceptive and witty, but my favourite is the film piece where, among other things, he explores why musicians make such bad actors. The Radio piece explores the strange worlds of John Peel and Simon Bates, and it's surprising who comes out best! Without being bitchy or silly, Thompson asks some hard questions of the kind of things both of them have done, opening our eyes to the inconstancies and silliness at work in the world of radio DJ-ing and advertising voiceovers. Having looked at pop music's position with the media, Thompson offers us a 130-odd pages of interviews, before five essays on musical themes. Here, shorter essays, reviews and interviews are combined and intertwined to support his theses. They're probably my least favourite part of the book: whilst never really becoming academic or too trainspotterish, they nevertheless head that way, and it's Thompson's voice we hear rather than his subjects. But - and I'm sure that's exactly what Thompson is doing - it is, of course, another 'way of hearing': via, or through, an intermediary. Thompson is certainly one of our best pop intermediaries; and this is a pretty good book. |

| Also celebratory and intriguingly diverse is Sampler 2 (Lawrence King Publishing, £19.95), a beautifully designed paperback presentation of work by another intermediary - the CD designer! It's taken a long time for the small CD format package to be used successfully and interestingly, but this book certainly proves that it's finally happened. Of course, some of the work here simply seems scaled down from LP [indeed, I'm sure some of the releases in here are available in vinyl; I know Primal Scream and Broadcast are] but much relies on the actual size and format of the CD - usually the digipack as opposed to the clear plastic case and tray. My favourites are Kim HiorthÀy's work for Rune Grammafon. Away from the pretentious scrap/note-book style of her own book, which Alistair reviews elsewhere in Tangents, her cool, minimal designs, with their odd blues and greens, warm red hues, scribbles and drawings, grabbing from both 50s design and 80s fine art, are a joy to look at; they make me want to buy the CDs - just to own the cover. Some of The Designer Republic's work for Warp seems to work in the same way; as does the sparser, typographical ECM-like design for a Pauline Oliveros CD. Isotope 217's covers are fine-art-retro, appropriating an appealing early-abstract-expressionist feel; elsewhere collage and blurred photography come into their own. Less successful are the naive cartoon illustrations of Laurent Fetis, a mix of 50s knitting design drawings and Pop Art via Yellow Submarine. Creation's in-house design offering for Primal Scream's Exterminator also does little for me. But I quibble. There may be no gatefold dragons and goblins, no huge band photos, or endless pages of lyrics [well, actually there are all of these around, aren't there? but, thankfully, not in Sampler 2], but this volumes shows the innovative and splendiferous artistic talents around that help persuade us to buy the music we listen to. |

| Less succesful is Mark Prendegast's The Ambient Century (Bloomsbury, £20). Subtitled 'from Mahler to Trance - the evolution of sound in the electronic age', Prendegast starts out with a woolly thesis that is never really defined, and by confusing Eno (and other)'s term 'ambient' and the idea of ambience throughout the book, finds space to include willy-nilly any and every band he feels like including. So what we get is a pretty ordinary historical overview of music. It starts promisingly enough, with a section entitled 'The Electronic Landscape', which begins with Mahler, Debussy and Satie, moves through the new instruments of Theremin and Martenot, the experiment and theory of Schoenberg, Webern and Vares² and on into the usual late 20th Century suspects: Cage, Stockhausen, Miles Davis, Xenakis, Feldman, Subotnick, Ligeti and Takemitsu. So far, so good, though we've read it all before, both in straightforward musical histories and better written books like David Toop's outstanding Ocean of Sound; Prendegast's writing is simply earnest and dull, a gathering of uninspired learning. Having sped us up to date in the contemporary classical world in merely 90 pages, the next section feels the need to backtrack to the 60s and focus on 'Minimalism, Eno and the New Simplicity'. So back we go to the well-trodden path that La Monte Young, Terry Riley and Steve Reich trod, before hearing yet again how Brian Eno invented ambient music and changed the world in the process, specifically influencing Harold Budd and Jon Hassell [which is odd, because both were involved in minimalism well before Eno heard it], and indirectly causing/inspiring ECM, Windham Hill and the new holly-minimalism of Gorecki, P¹rt and Taverner. Prendegast seems unable to separate the good from the bad. Wyndham Hill's jazz-muzak is set on a par with the careful production exercise and inspired jazz of ECM; I for one can't see what the limpid retro-Romantic music of Taverner has to do with the intelligent musical explorations of P¹rt. Because Prendegast has set up no clear rules of inclusion, no argument to justify, and no criteria for criticism or even personal taste, he is able to grab anything and everything he quite likes hearing and bung it in to the mishmash the book slowly turns to. He is unable to grasp the complex links and influences, the web of musical and conceptual fertilisation and inspiration at work in the 20th Century, and gamely plods on with some kind of vague timeline, every so often mentioning the word 'ambient' or 'ambience' incase we've forgotten the plot. But it's not the reader who has lost the plot. The third section 'Ambience in the Rock Era' is where it really falls apart. Did you expect to find The Rolling Stones in here? Van Morrison? David Bowie? The Doors!? I mean there may be some way of looking at the use of production and sonic ambience in, say, The Beach Boys' music, or the way feedback and noise are used to exhilarating effect by Hendrix [both are included here] but Prendegast doesn't even really deal with anything beyond 'mood' and 'surface'; he continues to confuse 'ambience' and 'ambient in the most simplistic and uninteresting way. So he gamely ploughs on through the work of the musicians he likes: Country Joe & The Fish, Tim Buckley, the Krautrock fraternity, progrockers; on, on, through the murky waters of synthesizer tosh like Vangelis, an eclectic 'Indie Wave' group that manages to include Cabaret Voltaire, Sonic Youth and Dead Can Dance!, to a ragbag of 'Individualists' that rounds up the usual suspects: Fripp, Gabriel, Lanois, Laurie Anderson, U2 and -get this! - Enya. No-one is spared the highest praise. There is no critical evaluation, no explanation of how they fit into 'the ambient century', just fawning praise and generalised description. The final section considers 'House, Techno and Twenty-First century Ambience' and is even worse. I'm no expert on techno and its many derivations and historical twists and turns, but I'm a Professor of House compared to this guy. Prendegast is really cruising now - free as a bird, with no critical line or ideas to hold him back; cruising effortlessly and senselessly through music he seems to have little understanding or love of. What a wasted opportunity this book is! It simply reads like an everyday history of rock and contemporary classical/jazz/crossover music, ignoring all the complexities and delights that these worlds offer. There is no-one in here you won't have heard of if you have ever read The Wire or Ocean of Sound, there are simply acres of territory the author seems totally unaware of. Where are the likes of Pere Ubu? Nurse with Wound and other collage/industrial bands? What about the 'ambience' of New York punk and the city's new/no-wave bands? But then I guess I'm falling into wanting to put my record collection into the book instead of his. Whatever, anyone who takes Enya and Vangelis seriously needs to take a holiday. Whatever it is, 'the ambient century' appears to not exist, and will be consigned - like the inflatable plastic chair on the cover - to ideas that never really took off; perhaps never should have even existed. Ambient has definitely not, despite the cover's claim, 'established itself beyond question as "the classical music of the future"; and this book makes little sense as a case for proving otherwise. © Rupert Loydell 2001 |