New York Eye and Ear Control | |

| The record: New York Eye and Ear Control. The label: ESP-Disk (ESP 1016, for the train-spotter inside me). Eye and Ear Control- images of pest control, surveillance, bugs, Burroughs, paranoia. A short leap to the Burroughs-influenced cut-up of early Cabaret Voltaire, doing the (Mussolini) headkick. Or the inflammatory 'termite art' championed by master film critic Manny Farber, the kind of raw-edged 'B' movie inventiveness trademarked by Don Siegel, Sam Fuller or Edgar G. Ulmer. The album sleeve features nocturnal movements, skeletal figures in silhouette, New York at night haunted by radioactive spectres, whose forces are marshalled by Ayler and his clan. This 1964 Albert Ayler set has been given the regal reissue treatment by ESP, who have burnished the master tapes in fine style. It's a cause for real celebration that this film soundtrack, along with the Art Ensemble of Chicago's unused soundtrack for the French New Wave film Les Stances ö Sophie, have finally been released from the traps on the cd format. Or on "shaving mirrors", as Radio 2's master of 1930's nostalgia Hubert Gregg would have them. The diabolically goateed Ayler leads the way on the recording, a point worth noting as facial hair is a fair indication of a jazz musician's credentials and intentions. Take Count Basie: an impeccably groomed moustache with an exclamatory gap between the two tufts of hair, an exuberant statement in itself. The quintessence of dapper, here 'Bugs' Bunny meets Clark Gable. Or Paul Bley, who sported a mighty mock-Nietzsche effort during his time with the great Jimmy Giuffre trio on the likes of the Free Fall lp. A real cool killer, he looked as though he could balance ice cubes on the shock of hair above his upper lip. Ayler's silver-toned flowing beard is altogether more troubling, a Moses who's seen the burning bush and is willing to testify on his saxophone. His scream-and-run brand of white noise pits his instrument against prosaic reality and promises revelation to any budding Bronx Bulls or Dead End kids out there. He's backed on this date by the knockout combination of Don Cherry on trumpet, the familiar bass-drum axis of Gary Peacock and Sunny Murray, and the sonic delights of Roswell Rudd and John Tchicai from the New York Art Quartet. It all adds up to something of a high kicking New York avant head charge. The album was recorded as the soundtrack for Michael Snow's underground film of the same name. The images may have disappeared from view- a great shame as Canadian 'termite' director Snow was also championed by Farber- but the music is still as stark and guttural as the 'free' era got. There is a clear sense of six musicians wailing the blues, performing high-wire antics in unison, celebrating the limitless expanses opened up by soulful music of this magnitude. |

| I love the grasp Ayler has of structures, echoes and resonances which make his music overspill any narrow category suggested by 'free jazz', a dead-end label. The Dixieland heritage is clear, but the strange brass band chatter could just as easily belong to that other New York pioneer Charles Ives, a man who ruthlessly pursued possibilities in music, mixing Emerson's high-minded ideals with the obsessive questing spirit of a Captain Ahab. Ultimately there's a deep blues sermonizing which Ayler summons up from his horn and the unified bleats and squawks of his contemporaries. New York conversations, a Saint Valentine's Day love letter delivered as gunfire from a bouquet of flowers. The way he, Cherry and co play here, in the throes of mortal passion, their music could just as easily speak of the charred wreckage of Ballard's Crash, Harry Crews's Car or the physical contortions of a bullfighter. Eye control: because this music generates visual scenes, action under pressure, the eye of the camera pulls down its shutter tightly over unexpected views. Leaping and loping outside the narrow confines of the cramped loft-space in which it was recorded, or the confined space in which I play the record now. Heat, sparks, soldering caffeine nerve-endings together, its clatter could stop the traffic on the M25 given half the chance. If I ever learn to drive, I'll have to put that theorem to the test in my trusty Alfa Romeo. |

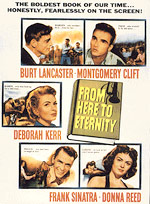

| Ear control: because the beauty lies in the ear, to borrow freely from Sonic Youth's. The intricate by-play between the horns and percussion, with details meshing into place several listens later. It demands attention and focus, until the earthly and earth-bound soar into another plateau. The presence of Cherry adds an unerring precision, staccato gasps of cornet glaring at the world outside, baleful, wailing, sounding a reveillée Montgomery Clift would have killed for in From Here To Eternity. Sounds to accompany John Garfield's famous daybreak prowl down Wall Street captured in Abraham Polonsky's Force of Evil, those silken movements leading him down, down, down, away from the city and syndicated corruption in that film. What were the words of John Prine's song? "John Garfield in the afternoon/ Montgomery Clift at night", the small-town boy needs heroes, myths, full of life, bigger than life. The music makes sense as profound statements of discord, primal discontent rising up from the shadow of monolithic skyscrapers. Control: a strange word to use in connection with 'free' music, but no less relevant. Pauses, repeated riffs, textures borne from sullen contours, mutinous explorations of shapes and spaces preceding architecture. These recordings tighten their grip, being assembled from individual impulses seeking expression outside fixed bearings, yet tied together in mutual regard. The group exercises control and unites its resources on listening and interaction, hence the strange black and white graininess, lulling the ears one minute, exploding outwards in dazzling profusion the next. When jazz musicians set about burying Uncle Tomism for good, and that included Louis Armstrong's patent leather smile, one of the main activists was Max Roach. Behind his drum kit on recordings with Herbie Nichols or the great trumpeter Clifford Brown, the facial movements were minimal, exuding austere self-control to all-comers. All the better to unleash tightly coiled riffs, trenchantly executed solos using cymbals and sticks for their own nimble fire power. Roach formed an uneasy alliance in the early 50's with bass behemoth Charles Mingus, and they formed a short-lived label, Debut Records. It enabled them to release much music that would have remained ignored, and his loyalty to Mingus remained visible on the powerful 'Money Jungle' Blue Note set. Here the pair were joined by Duke Ellington on piano, a mismatch of egos but their cumulative energies make it one of Blue Note's most highly prized issues. Roach is represented in drummer Art Taylor's very valuable compilation of jazz interviews Notes and Tones, where he stakes out his position in relation to snooty critics with characteristic force. Talking in 1971, he defends Mingus's intolerance of damaging write-ups: "A critic is taking his life in his own hands. Suppose he doesn't like the guy, but the guy has given everything God has given him to do the job and he says it's nothing. He's giving that man licence to kill him." |

|

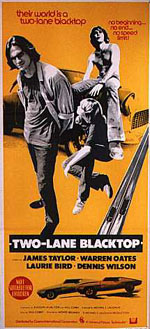

As an erstwhile defender of aesthetic decency in these pages, I'd like to think I was exempt from such charges. I'm also fascinated by the kind of scenarios that attitude could bring about. After all, Jean-Luc Godard didn't hesitate to beat up the producer of his Rolling Stones film for tacking on the full version of "Sympathy for the Devil" at the end of One Plus One. Enough empty verbiage has been written about his films too, which would go some way to explaining his marginal status, living and working in Switzerland, in isolated indifference from the film-making community. Yet I think of Lester Bangs, spitting vitriol towards MOR safety in his "James Taylor Marked for Death" piece. Justified contempt of course, but my mind's eye pictures a harder, leaner, hairier Taylor reading said article and doing something about it. After all, the man had enough kudos to star in Monte Hellman's awesome road movie Two Lane Blacktop, alongside Beach Boy Dennis Wilson and the mighty Warren Oates. Taking time out from his busy schedule for that film, where screenplay writer Rudolph Wurlitzer kept his lines of dialogue to a sparse minimum, Taylor pays Bangs a visit. He carries a copy of the offending magazine article, holding it up to our moustachioed critic. Tight-lipped, trench-coat collars up, fedora tipped forward over his head Alain Delon-style, he makes his way over to Bangs's highly prized collection of 33's, 45's and 78's. He calmly sets about his act of vengeance, leaving a trail of shattered shellac in his wake. Fists and arms flailing, Roach inspires a similar riotous m°lée at the drums. Seized by inspiration, each statement carries a rhetorical charge of some kind, an exclamation mark, sometimes a question mark, the occasional ellipsis... A seasoned veteran now, he still inspires with his ability to keep pace with the seismic pianistic shudders of Cecil Taylor, a true test of stamina. Roach's most prominent period would be the early 60's, where his forceful martial drumming was allied with gospel choirs and the primal vocalizing of his wife Abbey Lincoln. A heart as big as New York, and a technique as honed as Ayler's, his drumming can suggest a state of clamouring intensity and subside into nuanced accompaniment. His collaborations with Lincoln are as feisty and aggressive as you'd imagine, the 'We Insist! Freedom Now' suite co-written with Oscar Brown, Jr, followed by the Impulse! sets 'Percussion Bitter Sweet' and the glorious 'It's Time'.. While Blue Note cashed in on the blueprint laid out on Roach's gospel-infused 'It's Time' lp with Donald Byrd's slightly sweeter mix on 'A New Perspective', it makes sense to go back to that Impulse! label effort. Not as f°ted as the 'We Insist! Freedom Now' suite, where the exclamation mark was a knot of civil rights indignation and fury for change, Roach sets out his stall on 'It's Time' with total commitment. The sleeve pictures Roach in classic profile pose, the inscrutable shades speaking of fire in his belly and sticks of dynamite in his hands. The line-up assembled includes Abbey Lincoln on vocals on the album's closer, the jagged contributions of trombonist Julian Priester, Mingus acolyte Mal Waldron's piano and the awesome Clifford Jordan on tenor sax. Recorded in New York in 1962, it builds up a corrosive head of steam on the title track, with Roach firing off round after round of splenetic artillery. The pace is more contemplative on "The Living Room", with the lyrical trumpet calls of Richard Williams summoning visitors to feel at home, mix a drink and relax with like minds. In the background of "Another Valley" there's superb stormy playing from Waldron, bringing his hands crashing down on his keyboard for percussive effect. I suspect that he, like Cecil Taylor, would have found difficulty taking out insurance for his instrument during this period. Clifford Jordan's tone isn't quite Ayler bushfire, but possesses its own grandeur and charisma. On the Roach album he imbues the affair with a lyrical depth that spells out S-O-U-L with unflagging grace. His playing never fails to inspire, whether with Roach on these Impulse! sets, on the classic 'Blowing in From Chicago' for Blue Note with a Sun Ra-less John Gilmore, or guesting on Joe Zawinul's funkier 'Money in the Pocket' lp alongside luminaries Joe Henderson and Pepper Adams. His purity and directness nourished a legion of admirers. He remained Don Cherry's all-time hero, and I could swear his hard-blowing style left its mark on the young 'Gato' Barbieri. The youthful cat Barbieri had a fling with free blowing on the wonderful 'Complete Communion' set reissued by Blue Note, which featured him alongside Ornette's team of Cherry, Billy Higgins and Ed Blackwell. It's a rapid-fire lp, staccato playing conjuring parabolas of arching, arc (should that read ark?) forming sound colonies, ants tumbling from their instruments. Time to call in pest control. New York eye and ear control- for 40 minutes New York is everywhere. Eight million stories, a concrete jungle with its own fearsome poetry. Out on the street Albert Ayler stalks in black and white, his saxophone case doubling as a machine gun carrier. Torrents of notes, split notes, full-bodied notes, mutilated notes, propelled through his mouthpiece and into the open air. © Marino Guida |