I was pleased this month that the National Curriculum Tests for 14 year olds, which traditionally test kidsí ability to write for a specific audience, purpose and form, chose this year to ask pupils to write in the crime genre. Itís been interesting to see what kids have produced, what kind of preoccupations and interests, what kind of culture they present in their crime writing. Their stories donít show a pretty picture of Britain for young people (though as you might expect, their source of inspiration seems to be a mixture of ITV mini-drama and US cop-schlock, as well as the issues like peer pressure and parental instability they may have more direct experience of).

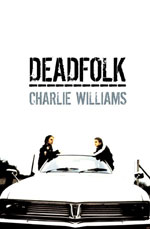

If crime writers are concerned with reflecting the worst of their contemporary culture, itís hard to think what a good modern British crime novel may look like. Depressing to think then, that Deadfolk by Charlie Williams might be something close to that.

Set in a provincial market town not unlike the sort of place weíre all a little wary of going to for a drink, the novel is chock full of lager, fry-ups, dodgy motors and rough birds, as well as rotting bodies, gang violence, incest and torture. What Charlie Williams has done well is this combination of recognisable English Saturday night High Street fare with the ingredients of the very blackest sort of crime novel. The extreme violence and frantic plot twists of pulp crime fiction fuse frighteningly well with the social problems of a Britain we can place. In fact, itís the social context that Williams places these pulp fiction elements into that make them believable, in a gothic sort of way.

Williams draws caricatures of the staple players of rural small town life: the head doorman, the local ≠ er- good time girl, the family of bruisers. These characters get the full treatment in Deadfolk and none of them come out looking like the salt of the earth. In a Chandleresque way Williams gives us reasons for the evil these characters do, though there are questions to be asked about the level of sympathy he has with any of them. Where Chandler and other writers like Ross McDonald judge and mete out justice to their unlikeable characters with a touch of sadness, Williams seems to have a more voyeuristic approach. Thereís a coldness in his depiction of this culture and it feels like heís exorcising some ghosts.

Itís a scary mirror Charlie Williams holds up to life in rural England, though itís scary in the best way of crime novels, a distorted fairground sort of mirror of a very English and contemporary kind.

© 2004 Carrie McMillan