(Or 'How Damien Hirst Tried Something New')

"I'm painting, I'm painting again.

I'm painting, I'm painting again.

I'm cleaning, I'm cleaning again.

I'm cleaning, I'm cleaning my brain.

Pretty soon now, I will be bitter.

Pretty soon now, will be a quitter.

Pretty soon now, I will be bitter.

You can't see it 'til it's finished

I don't have to prove...that I am creative!

I don't have to prove...that I am creative!

All my pictures are confused

And now I'm going to take me to you."

'Artists only' - David Byrne, Talking Heads

Somewhere along the roadside of the twentieth century there lays the wreckage of an unresolved argument. I am guessing the practitioners of this debate agreed to agree to disagree some time ago, each convinced of their own precocity. The subject of this discourse is art theory and it is a subject that polarises its intrigues like no other. Followers of each camp can be found everywhere. Check out the arts section of your favourite rag and no doubt you'll find either some privileged octogenarian raving on about the 'impotence' of contemporary art, or alternatively a trendy young thing tearing apart the semiotics of preserved mammals. They're called Art Critics and they can be found in a Sunday supplement near you.

I would be surprised if you could pin down any sort of rational dialectic amongst these people, anything approximating a model for what separates good art from the bad. The fact is the Art establishment ran away with the idea that anything goes a long time ago and the real nuances of art have been a moot point ever since. And yet it's hard to gauge this given the presentation of art within the modern society. Every year 'prizes' for art are awarded with the now typical aplomb of an Oscar, or some other hackneyed accolade. Art of any kind it seems has been subsumed into the establishment in way rather curious for something that is essentially a decorative medium. Or is it?

And what is art anyway? The humble craftsman may lay claim that anything created by the hand of man, that seeks to visually stimulate in some way, is art. On the other hand the modern artist may consider it to be anything that has the dubious honour of being deemed so by the 'artiste'. It would be disingenuous to pretend that these opposing views are in any way reconcilable. So let us concern ourselves with the latter, art with a capital A if you will, as it is amongst these practitioners that the debate seems the greater source of consternation.

The contemporary (shall we say 'Western') artist generally sees art as an essentially intellectual exercise. I will assume this as given. He or she can bestow upon anything they wish the often spurious charge of 'Art' if they so wish. It is an intellectual choice born out of a desire to communicate something. If a problem needs to be addressed then it can be done so by any means necessary and if the purveyor deems this to be art then it becomes so. Such an approach has given rise to what seems on the surface to be pretty vacuous stuff, but is it a simply victim of its own circumstance, or success even, a very genuine reflection of vacuous times? Or is the answer much more straight forward than that? that contemporary art has become mere posture, an extension of ego for egos sake. Or is that the same thing? Whatever the case art seems to be caught in a sort of stasis where as a form it is not developing. The delightfully acerbic Michael Collings is spot on when he explains; 'I can't think of an historical situation where all this has happened - it's a new problem. Art has had a wide public aspect before, of course, but the wide public world had some gravity and dignity. It's as almost as if we've now got to admit that what art was, it can no longer be. In ten years time we'll probably admit that it no longer exists, that we really have broken away from any need for it.'

There was a time when a man was held accountable for his art. If not the crown, then certainly the church would ensure the errant artist not step too far over the boundaries of good taste. So instead one would have to content oneself with experimentation in form, composition and technique if to satiate an internal desire for innovation and self-expression. As society has moved forward the constraints placed upon the artist have slowly withered, their cruellest fate often scorn or disdain rather than torture of imprisonment. For most parts such liberation has proved unproblematic. The Russian Itinerants had to contend with issues of funding, mild censorship and public suspicion, obstacles that almost acted as an incentive rather than a deterrent invoked to enforce the party line. Hogarth's more vitriolic works were brushed aside as political satire (which they estimably were) somehow separate from his more conventional portraiture (which was oft-overlooked entirely it might be added). World War 2 not withstanding Western art has been allowed to proceed pretty much physically unchecked, as long as it doesn't expect to get paid for it. So in the absence of any real clandestine censorship, art in the 20th century was able to carve out its tributaries in legion, pushing the boundaries of artistic expression further and further into the aesthetic fug. But while it may be easy to explain away something like Mondrian as the brutally logical conclusion of abstraction, it is not so easy when tackling art that has appropriated existing images, or objects, as their raison d'etre, Warhol, Duchamp or Hirst to name but a few. Art which deliberately sets itself apart from any existing narrative and insists on starting violently anew. It is from here that concepts of art become discombobulated and the idea of what is permissible as art starts to get more archly vitriolic. By this I mean that pure visual abstraction, in a traditional two dimensional sense, will often be tolerated as simple visual experimentation (Rothko for example) but once you enter the realm of mixed media, video installation or object re-appropriation the product suddenly demands a raison d'etre governed by something outside of aesthetics. Otherwise why would one bother?

However, this presumes that through an innovatory interpretation of art there lies the potential for deeper meaning, or indeed that a simple landscape can have no greater significance that that is obvious from the subject. Yet the irony here is that it is the progression of form alone that imbues the work with a progressive meaning. That to portray an idea figuratively is too straight forward a method to be considered profound and that only through a development of form can art truly offer meaningful resonance. But is such development (or 'meaning') enough to qualify 'good' art? This is what contemporary art seems to be saying, that art need not be a symbiosis of it's from and content, but may exist as pure un-objective profundity. That if it is abstruse enough then its technical inabilities become irrelevant. Its agenda is paramount - art as epistemology. How can we reconcile such a vicious shift in, not just form & subject, but its entire statement?

Damien Hirst admitted, quite casually I suspect, that he 'had nothing in particular to say' but that 'he wanted to convey this' anyway. Fair enough, but hasn't his all been done before, and in very much more imaginative ways? Take Isaac Levitan's 'Vladimirka Road', a painting of nothing much more than a road. Nothing too figurative, no explicit symbolism, just a road with a solitary figure poised at a set of crossroads. On the surface one could reasonably assume that the author too has nothing specific to say, that he merely wanted to convey the loneliness of the Russian landscape. Yet the pictures moves. It could be because the chosen landscape is inherently powerful as an image (the Russian countryside on a sinisterly overcast day), or maybe it is because Levitan was using this as a metaphor for the authors state of mind (which if so would be melancholic to say the least). The difference with this, as apposed to Hirst's take on 'nothingness', is that Levitan realises, consciously or not, that one cannot really have 'nothing' at all to say. One can not want to say anything, weighed down as one may be with an overwhelming sense of torpor or ennui, but to be genuinely speechless would involve some sort of complete mental paralysis. Hence Levitan paints a picture which conveys a dissatisfaction, restlessness or anxiety. This is not having nothing to say. Whereas Hirst's claims to nothingness are not backed up with a product that actually reflects his self proclaimed mood. He is hoodwinking us. His work is neither minimally wan nor nihilistically gauche enough to suggest anything approaching intellectual or emotional stagnation. They simply reek of contrivance. And this is the crux - if Hirst really had nothing to say then why would he even want to bother trying? His say so is not enough to be convincing because, even assuming it were possible, ones sense of limited expression could only logically distil itself into one finite piece of work. (David Bowie's 'Low' was his own take on the situation and he moved on from there very shortly afterwards). It could all be irrelevant anyway as I suspect Hirst was reaching for a sound bite when this was said. But it is indicative of the modern malaise in art where, without the cult of personality to justify the art, the works are left frustratingly tight lipped. Without the artist to establish a context then what worth is its face value? It's almost as if the modern artist works backwards, conjuring up a contrivance from which to display themselves rather than speak about something bigger than the self. Indeed some artists seem to have become frustratingly savvy to the barren coda they have come to inhabit. The Guardian cites Jake Chapman as saying of Charles Saatchi and his monolith to artistic narcissism that the Tate Modern has become a 'monument to absolute cultural saturation' and 'simply an expression of one man's ownership.'

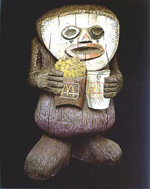

One of the more interesting approximations of what it means to be artistic I have found comes from that strange purveyor of art and music they call Billy Childish. I don't know a huge amount about Mr. Childish other than he paints, writes, records music and once dated Tracy Emin. Talking about his dalliances with the nuances of art he concludes: 'Authenticity is of far more worth than originality. In truth, originality only has a chance if you are first authentic.' A quote that seems to hint at some underlying atavism within the human psyche to produce art as exorcism, to create in order to satiate some primordial desire rather than make any contextual remarks. If this is true then art criticism would seem to be fighting a very difficult task - that of dissecting the inner recess of an artists psyche. So if the establishment cannot 'get it' then it has to find other means with which to appropriate art (which it does of course). So all bets are off it would seem, David Shepherd may rank alongside Warhol, conjoined through sincerity. I am not trying to sound cynical of Mr Childish because I think it a noble idea; that that which is honest with itself can be considered worthy of being called art, regardless of its apparent quality to others. And it would rid the art world of a lot of the contrivance that blights it if such a sentiment were to be taken on board by the art community. But surely somebody can be sincere and still produce bad art, can't they? For if self reverence is the only qualification for what art may be then all art becomes subjective. This may be true in a solipsistic sense but it is of no use when wanting to achieve a universal understanding of what art may be. Or, in practical terms, what we may allow art to be. And perhaps this is the crux; that art is what society affords it to be, and if something feels uncomfortably out of step with the times then its suffrage will be in dispute. The perplexing implication then is that the worth of a particular piece of art is not fixed, that it can mean different things to different people at different points in time. Great isn't it? But faintly ridiculous also. Maybe it would help to imagine what art can be not? It cannot be lazy, it should not please too easily, it certainly cannot be cheap and it helps if it toys with infamy. A certain picture is developing don't you think? Warhol has a lot to answer for but then that's measure of his genius. His art was a once in a life time offer that many an artist since has used as licence to flesh out their unsubstantial whims.

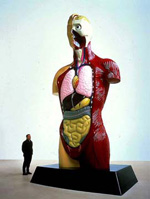

Hirst has just exhibited a series of pseudo-realist painting that he didn't even paint. He will argue that it is not important who actually transfers his ideas on to the canvas, that a painter is merely a conduit, an extension of the brush that applies the acrylic. Is he right? Can these new works carry the same weight of authenticity without coming directly from the hand of the auteur? For these ideas to then pass through a second party defeats the object surely? He can tell his minions what to paint, and to a degree how to paint, but these works will never be more than second hand appropriations of Hirst's ideas. And what's more, many of these works are merely representations of other works, be it photographs, tele-visual images and in some cases Hirsts own previous works. If he is making a comment on the dilatation of image then may I direct him towards Warhol's far more succinct fading screen prints of Jackie O, Monroe and Presley, among others. Or is Hirst just a charlatan, a hustler, convinced of his own misplaced importance within the art world. Because if this art really is just about the ideas or meaning, or even moods, then why doesn't he just tell us what these ideas/meanings/moods are, write them down or give a lecture or something. Maybe Collings is right and art as a truly meaningful tool is dead. Instead maybe it's better to simply define art as running the whole gamut of creative expression and leave it at that. And then the issue of whether it is good or bad art can simply be left to ones own taste.

© 2005 James Evans