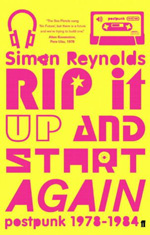

Rip It Up And Start Again: Postpunk 1978-1984, by Simon Reynolds (Faber)

- Charles Rennie Mackintosh, before he became rhythm guitarist for Crispy Ambulance.

I remember the first time I saw the word ‘postmodern’ and I remember just not understanding it. Because modern was, like, NOW, right? “This is the modern world”, opined St Paul not “was” or “will be”. Postmodern seemed to be, by definition, something that had yet to happen, art oozing through wormholes in time. Several years later, years of state-subsidised chin-stroking to the happy, happy sound of Rushdie and Nabokov and a professor who looked disturbingly like Roland Barthes, I kind of got the joke, but by that time postmodernism came free with every packet of cornflakes. The new Doctor Who is just one great big huggy Yeti of intertextual metanarrative, with lashings of extra homoeroticism, and kids in the playground can deconstruct like Derrida on crack (but they call it happy slapping).

So, yeah. This ‘post’ thing. After. Which immediately implies that it’s happening once something is dead and gone. So, Postpunk 1978-1984 safety-pins the shroud of punk at around the time the Pistols were disintegrating in San Francisco, despite the fact that at that point The Clash still hadn’t released London Calling. It’s official: the stumbling, stinky diehards who kept the flame burning throughout the following decades, like The Exploited or Peter and the Test Tube Babies - not to mention the new heads on the block like Nirvana, Green Day and, uh, Busted were, in fact, like Bruce Willis in The Sixth Sense-, dead without knowing it. That was your punk and two veg, that was. Now for afters.

And this is where the problem starts for Simon Reynolds, as he bravely attempts to create some kind of coherence the brief period of grace between Rotten’s “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?” and Geldof’s “Give us your fookin’ money!” Punk was a cohesive reaction against specific phenomena, from the Queen’s Silver Jubilee to Rod Stewart going disco. Postpunk was, well, stuff that happened after punk. Its motivations were many and various. There was, of course, music that followed on directly from punk in the sense that its instigators had been at the heart of punk for example, Public Image Limited and Magazine. And there were some acts, such as Joy Division, that clearly owed much to punk, but benefited from not having jumped on the original bandwagon, and had time to develop free from the clichés of flob and bondage.

Postpunk, in retrospect (and certainly from the perspective of alleged postpunk revivalists such as Franz Ferdinand and Interpol) is wrong-angled guitars and throbby bass the names to check nowadays are Gang of Four and A Certain Ratio and Wire. Funk for maths postgrads. But in Reynolds’ world, it’s really anything that happened in these six years that he quite liked.

Was punk really the big motivator for the likes of the Human League and Cabaret Voltaire, or was it cheap synths and Kraftwerk? What pushed the development of 2-Tone was surely the post-war demographics of the West Midlands: immigration + collapse of manufacturing sector_ Þ racism = ska revival. And what exactly links these musics with Scritti Politti and Devo and Eurythmics and Was (Not Was) and The Waterboys and ESG and Psychic TV and Art of Noise and Duran Duran and The Residents and Big Country and Bauhaus and Nurse With Wound except for chronological coincidence and, in some cases, a tendency to sing a bit like Peter Cook? If they were all postpunk, then either postpunk means nothing, or it means everything. If they were all postpunk, then so were Joe Dolce and the St Winifred’s School Choir.

Punk offered an example, a sign that the proles had the means of production at their disposal, but surely the most significant development here was Geoff Travis setting up Rough Trade. And, as Reynolds points out, Travis was nowt but an old hippy. Indeed, the most significant operators, it would seem from the narrative on offer, were the non-musicians. Malcolm McLaren hovers over the narrative like a malevolent pagan godlet his seedy manipulation of Bow Wow Wow, and his fascination (entirely theoretical, it seems) with paedophilia, made me feel retrospectively guilty over my adolescent crush on Annabella Lwin (and she’s older than me, for Christ’s sake). The initial success of Postcard and the Scottish New Pop is ascribed to the need for hacks Paul Morley and Dave McCullough to find something a bit more cheerful to think about after Ian Curtis killed himself, and from there it was but a step to Martin Fry’s gold suit. Incidentally, it’s a shame that, despite the blurb describing the author as “this country’s finest and most intellectually engaging journalist”, the best stylistic tropes that Reynolds can summon up are the work of others: Morley labelling David Sylvian as “too fragile to fuck”; Ian Penman’s image of Scritti’s Green Gartside, “disapproving of things, like an unwashed Pope”. In Reynolds’ bibliography, Lipstick Traces, Greil Marcus’s bold, flawed attempt to put John Lydon’s cackle in historical and aesthetic context, is conspicuous by its absence. It might not be so informative, if you’re revising for a GCSE in Punk And After, but Marcus’s is a better book.

Although, in a way, the facts-first, tinsel-free reportage style that Reynolds employs is appropriate. This is what happened. Make of it what you will, reader. Because postpunk didn’t rip it up. It took a scalpel, and calmly sliced up small pieces of yesterday’s media to create a neat collage but not enough to cause a fatal loss of blood. It was just a slightly more challenging task than that set by Sniffin’ Glue magazine (“here are three chords, now form a band”). For Orange Juice, the Four Tops and the Buzzcocks alike were just there for the borrowing. The funny thing is, it’s the Four Tops and the Buzzcocks, albeit each in a somewhat mutated form, that are still plying their wares, in an era that must now be postpostpostpostpunk, and then some.

© 2005 Tim Footman