Obviously, there is plenty of room for argument, and works can achieve both camp and irony, depending on context and perspective. Tony Christie’s ‘Amarillo’ was camp for many years; but surely he now sees that, which makes it ironic, if not bearable. William Shatner’s Has Been album is camp if you consider Shatner himself to be the author; ironic if you judge Ben Folds to be the dominant partner. Paul Anka’s Rock Swings could go either way; Anka’s smile is so suspiciously taut that it’s impossible to work him out.

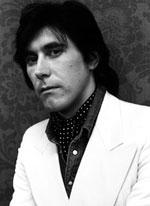

Bryan Ferry has been playing a similar game for the last 30-odd years. The lounge lizard schtick is an endearing landmark on the pop landscape, but does Ferry actually believe it? Will he ever return to his pit-village roots and declare, to tweak Peter Cook, that he’d rather be a miner than a crooner? We may never know.

This ambiguity of intent has seeped out from his work and into the critical discourse that surrounds him. The NME used to mock him as ‘Byron Ferrari’, but as Charles Shaar Murray recently admitted, Roxy Music was one of the few relatively mainstream bands of the early 70s that the hacks really loved. So why did they take the piss? Well, you may as well ask Ferry why he wore that gaucho hat.

There even seems to be a critical re-evaluation (which predates Bill Murray’s karaoke rendition of ‘More Than This’ in Lost In Translation) that sees previously overlooked validity in Roxy’s late 70s/early 80s output. Whether this viewpoint in itself is camp or ironic or (God forbid) sincere, I’ll go on record and say that it’s wrong. Roxy still made some good records after Eno left (after the second album, For Your Pleasure), but as with post-Syd Floyd and post-Cale Velvets, they ceased to be particularly special. Eno, feather boa, notwithstanding, was undoubtedly ironic, coolly aware of the louche subversion he was inflicting on the frugging hotpants in the TOTP studio. His lack of technical competence (check out that synth solo on ‘Re-Make/Re-Model’!) was no barrier to the influence on what Roxy was about.

But by the end of 1974, and the release of Country Life, Eno was long gone, and the ambiguous(ly?) female cover stars of the early albums had been replaced by catalogue smut. The single, ‘All I Want You’, is a decent slab of stomping glam, although Phil Manzanera’s squalling solo heralds the fact that this ain’t The Sweet.

And then, as the song tucks in its elbows and heads for the home straight, Ferry leans towards the mic and coos “Toujours, l’amour, toujours.” Now, rock ‘n’ roll is such a defiantly Anglophone genre that any deviation is worthy of consideration. Is Ferry acting out a conscious stereotype, all onions and beret, whispering his lust to a coquette called Fifi (who doubtless responds with a giggly “oo-la-la”)? Or is this the beginning of Ferry as matinee idol; the miner’s son who believed that an Antony Price tux and a French O-level would really enable him to cop off with Jerry Hall?

Or maybe it’s just a transcendent moment of madness, spontaneous babble, neither camp nor ironic, but both at once? The issue, for a few seconds, isn’t whether or not Ferry knows how daft he sounds, but whether he cares. This is the sound of a man utterly wrapped up in his performance, so nobody, least of all himself, can see where Bryan Ferry ends and ‘Bryan Ferry’ (or, for that matter, ‘Byron Ferrari’) begins. And, incidentally, the singer’s lipsmacking relish at his own abject gorgeousness effectively undermines the title. All he really wants, and needs, is Bryan.

© 2006 Tim Footman