Some people have conversions along the road to Damascus, so to speak. Other people seem to be forever in a naturally cool place. And there can be no better example of that than one Adrian Sherwood, a teenage reggae fan from East London who didn’t look back.

Back in the day when I was in scavenging mode, I’d hunt around and among the boxes of 10p singles abandoned in what was then Record and Tape Exchange. I’d particularly be on the lookout for any old reggae, soul, punk, and was always particularly taken with anything on the Carib Gems label which seemed to crop up occasionally though all too often looking as though a heavy goods vehicle had been using the vinyl for a skid pan workout.

Carib Gems had a particular place in my heart for putting out the Carroll Thompson set, Hopelessly In Love, which was the quintessentially English lovers rock record, but I hadn’t realised that it had been a finishing school of sorts for Sherwood. Certainly by the time that Carroll Thompson set was released Sherwood was already embroiled in realising his vision of a new reggae music. He was putting to great use the connections he had made ducking and diving, wheeling and dealing in the roots reggae scene.

Already in 1978, before the Pop Group, Slits, and PiL had put records out, Sherwood had sprinkled gold dust over the earliest recordings by loose reggae collective Creation Rebel as well as the first instalment of the Cry Tuff Dub Encounter by the legendary Prince Far I. In true punk pioneering fashion Sherwood made his inexperience work for him, and sought to translate the ideas in his head about how music could sound into a reality.

The names associated with Creation Rebel would go on to recur throughout Sherwood’s career, and the names like Crucial Tony, Lizard, Bonjo, Eskimo and Style would take on mystical proportions. The tangents that have been explored since the first Dub From Creation outing are tangled and troublesome for achivists but a delight for anyone in love with musical exploration.

While the early Creation Rebel sets came out on Sherwood’s Hitrun label, it would be the On-U Sounds set up that would be the imprint most closely associated with his name, and its legacy is phenomenal even if its attention to detail is a little lacking with many essential releases yet to be satisfactorily salvaged. There are no doubt all sorts of legal and licensing reasons for this, but it is frustrating not to have titles by Judy Nylon, Mark Stewart, and Annie Anxiety unavailable.

The Sherwood/On-U Sounds associated records from Creation Rebel, and its tributaries like African Headcharge and Dub Syndicate from the 1980s still sound incredible. They take reggae as a template, but drag it into all sorts of strange places, by bringing in all sorts of strange found sounds. These records were, despite the cliché, literally light years ahead of everything else around, and certainly not for purists of any hue. One has only to listen to Creation Rebel’s Starship Africa, African Headcharge’s Drastic Season, Singers and Players’ Revenge of the Underdog, and Dub Syndicate’s Tunes From The Missing Channel to understand how true this is.

In the early days Sherwood would farm out his productions to any receptive outlet, such as New York’s 99 Records and ROIR International, and our own Cherry Red and Situation 2. One of the joys of Sherwood’s way of working was that he would emerge under a variety of guises as the years went by, inverting the natural desire of artists to bolster their ego. Thus a series of Sherwood classics appeared under disparate names such as Playgroup, Voice of Authority, and Missing Brazilians, which are absolutely essential and right out there. The last two of these featured vocal contributions from one Shara Nelson on vocals, way before Massive Attack days.

Sherwood’s key collaborators are fascinating. They could be as diverse as keyboards ally Nick Plytas from pub rockers Roogalator (and later the arranger behind the great Anne Pigalle) and improv heretic Steve Beresford to reggae legends Prince Far I and Dennis Bovell, and it’s certainly worth arguing that it was close colleagues and partners Kishi Yamamoto and Pete Holdsworth that helped realise Sherwood’s high ideals and crazy dreams.

I’ve read Sherwood describe his brand of dub as being equally influenced by the sounds of The Fall and Captain Beefheart as by the music coming out of Jamaica. Given the spirit of the age, it’s no surprise to find therefore that representatives of the Pop Group/Slits/PiL axis of adventure recur throughout the On-U discography to great effect. It was with the Pop Group’s Mark Stewart though that Sherwood had the most fruitful partnership, notably with the Learning To Cope With Cowardice set where the backing was provided by Creation Rebel as the Maffia.

Future Maffia outings on Mark’s records would be provided by the former Sugarhill core of Doug Wimbish, Skip McDonald, and Keith LeBlanc, who would broaden the reggae base of On-U’s sound and take it into even more futuristic areas with the ramifications of electro/hip hop/p-funkindustrial dub. The Sugarhill pioneers (and remember these were the people who had provided the music for classics like The Message there, so how perfect was it that they were working with Sherwood?) also appeared with Sherwood and crew in a variety of guises such as Tackhead and Strange Parcels (where they worked with vocalists like highland warrior Jesse Rae who wrote the classic Inside Out for Odyssey, Bernard Fowler from the Peech Boys, and Basil Clarke from Manchester’s Yargo).

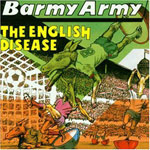

The strangest collaboration surely though was with Sherwood for his Barmy Army/English Disease set, a football themed record which must have seemed a trifle bizarre to some of the New York/Jamaica ex-pats participating on the record. Quite what they made of Sherwood’s songs of praise for West Ham legends like Billy Bonds, Alan Devonshire, and Leroy Rosenior is something to ponder, but if like me you are of a claret and blue persuasion and getting on a bit, then six minutes of Billy Bonds MBE will have you in floods of tears everytime. And a version just before that of The Liquidator as reimagined by Keith Levene somehow joins the dots perfectly between some important strands of popular culture.

Like all true music obsessives Sherwood took every opportunity to share his love of music, and the possibilities presented by the advent of the compact disc meant he was able to follow the lead of the Blood and Fire collective and set up with partner Pete Holdsworth the reggae reissue label Pressure Sounds, which like Kent with soul music made a whole genre of music attainable for new audiences who were not able to indulge serious vinyl collecting cravings. And importantly they made this music available in a very aesthetically attractive and informative format. You can pretty much pick up any Pressure Sounds CD (and indeed the Maximum Pressure imprint for more recent digital era classics) and know you’ll get access to some of the most beautiful ever, collected for all the right reasons.

While undoubtedly Sherwood has worked on records and remixes that help pay bills, you get a pretty good sense that there’s something special going on, such as with Primal Scream’s Echo Dek so you’re left wondering what might have happened if he had been involved with the group at a much earlier stage? Nevertheless some of Sherwood’s finest moments are buried away on recordings by the likes of Akabu and Samia Farah.

And whether you’re looking backwards or forwards, there is always a different Sherwood path to explore, whether it be stumbling over a CD compilation of early recordings Sherwood made with the visionary George Wadada and Suns of Arqa, or where the Sherwood influence permeates recordings of Smith and Mighty or Digital Mystikz. Yet some people prefer the tried and tested.

© 2006 John Carney