I think Sam Prekop is just about the best thing in pop ever. And like all the best things he somehow signifies something deeper. So he may produce the most gorgeous, loping sunkissed songs, but those songs are rooted in a very open, creative, adventurous soil. So you end up asking yourself why others choose not to try the soil there?

Sam Prekop’s solo LPs are perfect pop. There are beautiful bahian ballads, haunting folk melodies, exotic flavours woven into beautifully constructed songs, and much more. Just about everything. Every trick of the trade Prekop has refined over a long period fronting The Sea and Cake, just about the best pop group ever.

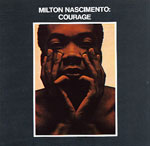

Over the years we’ve learnt that Sam’s roots are in the Chicago soul and sweet barbed beauty of Curtis Mayfield, the elegance of the Velvets’ third LP, the melodic invention of Miles’ Filles De Kilimanjaro, and the adventurousness of King Sunny Ade’s Juju Music, where he weaves all sorts of things like hawaiian guitars, surf music and dub trickery into the Afrobeat mix. Such detail is important, but means diddley squat were it not for Prekop’s way with a song structure. When you can write songs that good, it becomes a bonus to know the genius behind them likes Shuggie Otis, Milton Nascimento, Sun Ra, and The Congos as much as you do. Otherwise it’s just namedropping.

Since the early ‘90s Sam and The Sea and Cake have produced a steady stream of records that are magnificently melodic and archly adventurous, while being estimably and ineluctably The Sea and Cake. Because of geographical, label, and personnel connections they have been for better or worse tied up with other outfits. To their advantage, perhaps, sharing a label, members, and space with the likes of Tortoise has helped raise The Sea and Cake’s profile. To their detriment, however, being associated with the likes of Tortoise has meant they are weighed down by unwarranted generic descriptions, overused through laziness.

Tortoise it is easy to forget did at one time seem to be ones that might shake popular music up a bit. And while their early records may still delight, once in a while, the real importance again of the group’s approach was that of a real hunger, a hunger for all sorts of sounds that were outside the traditional rock format. It was no big artistic statement, but more a genuine enthusiasm. An enthusiasm to absorb and utilise everything from the then (mid-‘90s) underheard Krautrock, John Fahey and Ry Cooder’s Paris Texas soundtrack, Art Ensemble of Chicago and Herbie Hancock’s Mwandishi, the fire music being salvaged by Impulse!, bossa nova and tropicalia, Steve Reich and Terry Riley, English progressives like Henry Cow and Robert Wyatt, Augustus Pablo and Ennio Morricone, King Tubby and the Penguin Café Orchestra.

Perhaps most fascinatingly Tortoise reignited interest in jazz fusion, which up to that point beyond punk had been almost the ultimate taboo. But Tortoise made it more than acceptable to love some early Weather Report sets, Chick Corea’s Return To Forever, Tony Williams’ Lifetime, Herbie Hancock’s Headhunters, Stanley Clarke’s Schooldays, in the same way that A Certain Ratio had promoted American funk sounds and gradually perfected their techniques so that they almost merged with the contemporaneous jazz funk greats, fascinatingly seemingly submerging their own identity in the process.

The intriguing thing about Tortoise’s sound was that it had evolved out of a very specific and austere hardcore punk background. The group’s members had become gradually disenchanted with the rigidity of rock, and the oppressiveness of loud guitars and aggressive vocal delivery. The revolt away from this form was spurred by a growing fascination with the sort of thing Adrian Sherwood was doing with reggae with his On-U productions, and an awareness of how adventurous the underground had been with labels like Rough Trade and artists like the Red Crayola. This revolt was perhaps triggered by the pained patterns of Slint’s Spiderland, and appropriately that group’s David Pajo would later play with Tortoise.

The Tortoise sound, like say Joy Division and Massive Attack, naturally had all sorts of repercussions. Some were good, like closely connected Chicago comrades Isotope 217 and Directions In Music. Others were grim, like some of the acts on the Kranky label that would literally drone on and on, without any semblance of groove.

Much of The Sea and Cake’s groove has come through drummer John McEntire, the resource shared with Tortoise. While the high profile of McEntire helped open doors, the irony was that he was the last piece of the jigsaw as far as The Sea and Cake was concerned. The group was started by guitarist/singer Sam Prekop with bassist Eric Claridge in 1993 using funds provided appropriately by the Rough Trade label. They recruited old comrade Archer Prewitt on guitar, and only then added McEntire on drums.

Delightfully Sam’s background was in anything but hardcore uproar. He’d come to Chicago to study art, a passion he has maintained ever since, and gradually got involved in music and specifically Shrimp Boat, one of the most intriguing and enchanting groups of the late ‘80s/early ‘90s. Via the salvage work of Aum Fidelity we’ve now been able to hear so much of Shrimp Boat’s richness and craziness. The abstruse sound madly mixes up straight pop with bluegrass, free jazz, folk ballads and blues in the most mad way, so that you are hearing Captain Beefheart, the Carter Family, Talking Heads and Don Cherry all at once. Something wonderfully different.

Pretty soon Tortoise ended up in a cul-de-sac, going nowhere new, and one of the few people to follow through on clues was Atlanta’s Scott Herren who in a number of different guises would explore territory identified by the instrumental dynamics of the Chicago Underground. As Prefuse 73, Herren (interestingly with help occasionally by Tortoise’s John Herndon and even Sam Prekop) refracted and shattered hip hop and a host of different flavours, occasionally wonderfully, sometimes irritatingly when it seemed he was just about to give us a killer pop number, he’d tear up the plans and stick things back together frustratingly wrongly incomplete, depriving us of the opportunity to know if Herren could cut it next to the Timbalands or Neptunes. As Savath & Savalas he developed his sound into a gorgeous loping latin affair (sung in Catalan by Eva Puyuelo Muns) underlain with crackling electronica in a very Sam Prekop way, and something approaching Sea and Cake pop perfection.

For me, Michael Head and the Pale Fountains, Simon Booth with Alison Statton in Weekend, and Simon Topping in A Certain Ratio, and Paul Weller helped trigger an occasional infatuation with bossa and Brazilian music back in the early ‘80s. It’s an interest that’s waxed and waned over the years, as it has done for many people. The explosion of the salvage society and the internet information explosion have naturally made it that much easier to learn about and hear old records by Joyce, Nara Leao, Caetano Veloso, Edu Lobo, Tom Jobim, Elis Regina, Jaoa Bosco, and so on. Sometimes it seems it’s all one needs to listen to.

Sam Prekop perhaps feels plagued by comparisons to old Brazilian bossa records, and it is all in so many ways lazy journalism, but it’s also an incredible compliment to be mentioned in the same breath as Jobim, and to conjure up images of the Black Orpheus soundtrack, and I think Sam would be the first to approve of someone reading a review of his solo sets and then going out to buy Milton Nascimento’s Courage.

© 2006 John Carney