Lust for Life |  |

| With the festive season looming large one thing which springs to mind in connection with said time of year is reruns of musicals - you know the scene, Julie Andrews singing 'Edelweiss', Gene Kelly performing acrobatics with an umbrella. Funnily enough Kevin Rowland cited The Sound of Music as one of his favourite films in a recent interview, to accompany the earlier Dexys reference to that "special song" from Brigadoon in 'Love Part Two', one of the extra tracks on the reissue of Too-rye-ay. I'd speculate that the song in question was 'Almost Like Being in Love', and it does capture that towering feeling, the swoop and soar of the camera round a deliriously ecstatic Gene Kelly. It's one of the great musical moments, but the cynic inside me is aware of the all-important "almost" in the title, as loaded a touch as Gene Clark pointing out that he'd "probably" feel a whole lot better when she was gone. |

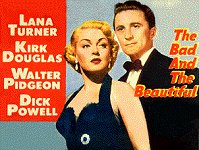

| So I hope it's not too incongruous for this website to include a little appreciation of Vincente Minnelli, probably my favourite director of screen musicals, responsible for Brigadoon and whose visual abilities were channeled into some of Hollywood's most scabrous melodramas. Kenneth Anger, Robert Aldrich, Billy Wilder, they all reveled in making films which gave the system a serious kicking, sharp words, biting images, all the more powerful for being delivered from inside the institution. Minnelli worked his critique into two companion films, the wonderfully titled The Bad and the Beautiful and the later expose of Cinecittà Two Weeks in Another Town. The former has the charm and innocence of a director in a position of untouchability, and reveling in that supreme confidence. Made under contract for MGM, for whom he'd scored the notable successes of The Band Wagon (the dapper Fred Astaire standing as his alter ego during those more carefree times, blithely elegant, singing standards like 'I Guess I'll Have to Change My Plans' and 'Dancing in the Dark' which hint at the bleakness to come) and the series of films featuring his wife Judy Garland. The Bad and the Beautiful showcases some of the features which are most characteristic of Minnelli's later, more world-weary style. The formal beauty and pristine clarity of the black-and-white images and the evident attention to the details of studio life, the costumes and the cameras towering over the mortals wearing them, are steadily undercut by the creeping note of disenchantment. Whereas the director's most commercially successful films seemed to celebrate the spirit of all-American wholesomeness which was the central dramatic scene of films such as Meet Me in St. Louis, the focus shifts to interrogate the position of the artist within a commercial system, along with the status of his art. Even Meet Me in St. Louis met with censorship problems - the scene where the petulant child destroys her snowman creation, singing "have yourself a merry little Xmas! It may be your last" was altered by studio heads with cold feet. What becomes most disturbing in those later films is precisely the concern with the artist's neurosis, liable to spill over not into dramatic expression but its flipside - psychosis, chaos, violence. |

|

Hence the position of Kirk Douglas in both the filmmaking critique films and the marvellous Lust for Life. You could wonder what on earth Hollywood was playing at, attempting to render the life of Van Gogh on screen, especially a lumbering doorstop account like Irving Stone's mammoth original novel. What surprises about the film now is how far removed it turned out to be from later treatments of the tortured Dutchman's life, the sickly Don 'American Pie' McLean's song 'Vincent' for instance. The primary focus in the film is on attempting to find a genuinely cinematic equivalent for the states of mind transferred to those canvases. Hence the attention to the colour scheme in the film, using a faster film stock which would capture a brighter, more dazzling yellow for the scenes in the cornfield. Of course the most dramatic scenes in the film belong to Kirk, who in tandem with Minnelli fine-tuned a portrayal which spits rage and contempt for bourgeois trifles - the most intense moments of the film almost make you forget that you're watching cocksure Kirk, and you become aware of a far more bruised, vulnerable force which he rarely drew upon. It is of course a hallmark of the collaborative spirit which existed in those films, and an openness to levels of imaginative empathy which the director dug deep to expose and encourage. On the razor's edge. And over it. It's something which also comes through in his lavish adaptation of Madame Bovary, with the wonderfully saturnine James Mason and Jennifer Jones as the spoilt heroine of the title. While her performance isn't as convincing as the gun-crazy role of Ruby Gentry in King Vidor's searing melodrama, it still reminds you of why Bobby Gentry changed her name and wrote the deep dark account of small-town weirdness, 'Ode to Billie Joe'. Which begins to sound like I'm advocating 'art' as exorcism - not exactly true, more a reminder that great moments of music or on film come from finding the ability to rage correctly. Like Momus drawing on Joe Orton or taking a well-established form and pulling it apart, reshaping it so that says something urgent. All the news that's fit to sing - the news being it's time to change your life. © Marino Guida 1999 |